The Million Dollar Club

Suspended summer bass make $1 million payday

Earning a membership to the posh brotherhood of million-dollar anglers is a career goal only a handful of professional bass anglers have been fortunate enough to achieve. Some pros have been knocking at the golden gate for decades but have never managed to crack the code to open it.

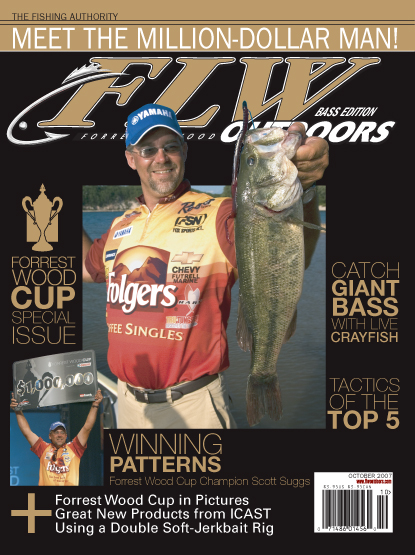

In a history-making performance, Wal-Mart FLW Tour Folgers pro Scott Suggs of Bryant, Ark., accomplished the lofty feat in just four days as he parlayed 17 bass and an intimate knowledge of Arkansas’ Lake Ouachita – a reservoir he has been visiting since he was a toddler – into a 2007 Forrest Wood Cup victory. The win, Suggs’ first at the Tour level since he began competing on the circuit three years ago, produced the single richest payday in competitive bass fishing history – $1 million.

Suggs won the tournament after turning in flawless performances on days one and two that advanced him into the final 10 in second place with 26 pounds, 8 ounces. He was less than 2 pounds behind well-known pro Jack Wade of Knoxville, Tenn.

Suggs won the tournament after turning in flawless performances on days one and two that advanced him into the final 10 in second place with 26 pounds, 8 ounces. He was less than 2 pounds behind well-known pro Jack Wade of Knoxville, Tenn.

With weights zeroed and the field cut to the top 10 for the final two rounds, Suggs poised for the strike on day three by catching the field’s only limit (11 pounds), which provided him a solid, 4-pound lead over Pedigree pro Greg Pugh of Cullman, Ala.

The personable pro managed only two keepers on day four, but one of them was a 4 1/2-pound toad that gave him the critical padding he needed – and then some – to seal the deal and hold off a final charge by Castrol pro Darrel Robertson of Jay, Okla. The final scores were Suggs with 17 pounds, 1 ounce and Robertson with 12 pounds, 8 ounces.

Suggs’ masterful performance serves as a testament to why he was one of a handful of local qualifiers heavily favored to win the world’s richest bass fishing tournament held Aug. 2-5 on what has to be one of the most scenic impoundments in the country.

Pretty as it is, however, Ouachita has a reputation for being tough as nails during the heat of summer. The water temperatures often crack 90 degrees, and heavy weekend boat traffic is known to throw the bass population into a stubborn state of lockjaw that can tax the patience of even the most seasoned anglers – but not Scott Suggs; not this time.

Never mind the relentless heat wave that swept across the Ouachita Mountain valley as the tournament got under way. Forget the flotilla of local spectator boats (as many as 50) that tailed him throughout most of the event. Disregard the proverbial home-lake jinx and the mind-boggling $1 million prize on the line. Suggs maintained his composure through it all as he executed a cunning strategy he had planned out in his mind long before the tournament began.

Interestingly, Suggs’ strategy was centered on something entirely different than what a high percentage of the field selected. Rather than focusing on grass, he directed most of his attention to a series of deep, offshore structure spots that consisted of underwater timber lines, points and humps spattered with isolated brush piles.

Interestingly, Suggs’ strategy was centered on something entirely different than what a high percentage of the field selected. Rather than focusing on grass, he directed most of his attention to a series of deep, offshore structure spots that consisted of underwater timber lines, points and humps spattered with isolated brush piles.

“I ruled out the grass deal before the tournament even got started,” Suggs said. “This was a weird year in that the lake stayed high for so long that the grass didn’t form a canopy on top. There were some fish in the grass, but not enough that I thought it could be won there. The hydrilla was shooting straight up. With no canopy, there was nothing to slow the fall of a jig and give us a good flipping bite. The high water also kept the frog bite in the milfoil from being a big factor.”

As badly as the conditions hurt the grass bite, they played right into the hands of Suggs, who probably knows Lake Ouachita and the habits of the bass that live there as well as anyone on the planet.

When his grass bite wasn’t materializing during practice the way he thought it should, Suggs called on his wealthy memory bank for an explanation.

“I knew from past experiences that there was only one thing that could have happened,” Suggs said. “The fish had suspended in the trees.”

Suggs confirmed his suspicions on his third and fourth practice days as he ran from spot to spot  checking “old breaking holes.” He soon began developing a couple of patterns to fish them. Most of the areas consisted of deep timber lines where the fish had always been prone to school on the surface once water temperatures began to lower during fall.

checking “old breaking holes.” He soon began developing a couple of patterns to fish them. Most of the areas consisted of deep timber lines where the fish had always been prone to school on the surface once water temperatures began to lower during fall.

“I basically spent that time going from place to place, looking and waiting to see a shad move or a fish boil to tip me off in some way,” Suggs said. “If I didn’t see any movement, I would throw on the place. If they were there, I would catch one within three casts and move on to another spot. That’s basically how I fished this tournament; I never stayed in a spot longer than 10 minutes if I wasn’t getting bit.”

Suggs did enough scouting in two days of practice to locate as many as 20 to 25 areas with potential to produce. About 20 of them revolved around submerged cedar trees in 35 to 70 feet of water. The magical depth was 22 feet. He also pinpointed a handful of main-lake points and humps where the fish had suspended around deep grass or isolated brush piles.

“I had my plan nailed down by the Friday before the tournament started,” Suggs said. “I stayed away (from the trees) after that. I spent the rest of my practice fishing grass, just to make sure it didn’t develop into something I needed to know about.”

Suggs narrowed his bait selection to three: a 3/4-ounce War Eagle firecracker spinnerbait with a No. 6 hologram willow-leaf blade and a gold Colorado blade; a plum Berkley 10-inch Power Worm; and a cherry seed Zoom Ol’ Monster worm. He rigged the worms Texas style in combination with a 5/0 Mustad offset hook and a 3/8-ounce Tru-Tungsten weight.

Suggs narrowed his bait selection to three: a 3/4-ounce War Eagle firecracker spinnerbait with a No. 6 hologram willow-leaf blade and a gold Colorado blade; a plum Berkley 10-inch Power Worm; and a cherry seed Zoom Ol’ Monster worm. He rigged the worms Texas style in combination with a 5/0 Mustad offset hook and a 3/8-ounce Tru-Tungsten weight.

He worked the spinnerbait on a 6 1/2-foot medium-heavy Shimano Crucial rod with a Chronarch reel. The worm rod was a 7-foot heavy-action Crucial topped with a Shimano Curado. His line of choice was 15-pound-test fluorocarbon.

Enticing the tree fish to bite was all about timing, presentation and retrieve. Casts had to be on the money, and the lures had to be counted down precisely to reach the magical 22-foot depth at which his Lowrance LMX-28C told him the bass were suspended. Suggs counted the spinnerbait down for 16 seconds and the worm for 20 seconds.

The spinnerbait, which produced roughly 50 percent of Suggs’ creel, worked best with a series of erratic retrieves. Most strikes came on a slack line, just after the lure contacted wood.

“When I threw left or right of the tree, I would burn it a few cranks, kill it and count it down to about five,” Suggs said. “Or I would slow-roll it a little ways, then jerk it up and count it back down to five. When I threw over the tree, I would count it down and climb the tree with a slow roll. When the bait broke over a limb, I would jerk it hard or let it fall.”

Suggs kept his worm on the move as well. He counted the lure down on a tight line and then reeled it slowly through the maze of limbs until a slight “tick” signaled a bite.

“When I felt the bite, I would point the rod straight at the fish and let it take up the slack,” Suggs said. “That’s when I would set the hook.”

“When I felt the bite, I would point the rod straight at the fish and let it take up the slack,” Suggs said. “That’s when I would set the hook.”

To keep his discovery a secret from other competitors, Suggs spent much of his practice time fishing undercover from a friend’s boat. He launched well after daylight and made sure no one was hanging around the Brady Mountain boat ramp when he loaded up before dark.

On numerous occasions, Suggs witnessed other competitors pass by within casting distance of the borrowed silver Ranger, oblivious to whom they were passing. Not surprisingly, Suggs’ assumed absence from the lake fueled a rumor mill among the field. Phrases like, “Anyone seen Suggs?” and “When is Suggs going to start practicing?” were among the pre-tournament chatter.

“I wasn’t worried about someone coming in on my spots, but I was concerned about someone seeing me out there and tipping them off to what I was doing,” Suggs said. “These guys are smart. If someone saw me, I knew there was a chance they might go someplace else and duplicate it. There was a tremendous amount of planning that went into this deal.”

Suggs’ plan worked masterfully throughout the first three days as he boxed consecutive limits and entered the final round in good position to win a life-altering sum of money. That’s when the winds came, which made it impossible to work his trees effectively on the final day.

“The wind really blew the last day, and it made it difficult to keep in contact with what the bait was doing down there,” Suggs said. “Plus, all the boat traffic shut the fish down. It would have been real easy to panic at that point, but I didn’t. Once I saw I wasn’t going to catch them out of the trees, I decided to devote my morning to structure-fishing.”

“The wind really blew the last day, and it made it difficult to keep in contact with what the bait was doing down there,” Suggs said. “Plus, all the boat traffic shut the fish down. It would have been real easy to panic at that point, but I didn’t. Once I saw I wasn’t going to catch them out of the trees, I decided to devote my morning to structure-fishing.”

Suggs picked up the spinnerbait periodically, but it was the Berkley Power Worm that iced the win. His first of two keepers came at about 9 a.m. off an open-water point in 26 feet of water that had been good to him all week long.

“Catching that fish was a big help; it helped me focus,” Suggs said. “My mind started to click at that point, and I began to think about some places that I hadn’t thrown on during the tournament and I knew nobody else had found.”

One of the first that came to mind was an oak brush pile he’d sank four years ago on a fast break in 26 feet of water. He went there about 10:30 a.m. and stuck a $1 million bass on the second cast. It weighed about 4 1/2 pounds.

“I never even idled over that spot during practice,” Suggs said. “I just had a gut feeling that I should try it, and it worked out pretty well. My wife, Kim, has renamed the spot the `Million-Dollar Hole.'”

Day 1: Five bass, 14 pounds, 14 ounces (three on spinnerbaits, two on worms)

Day 2: Five bass, 11 pounds, 10 ounces (four on spinnerbaits, one on worm)

Day 3: Five bass, 11 pounds (three on spinnerbaits, two on worms)

Day 4: two bass, 6 pounds, 1 ounce (both on worms)

Suggs’ keys to victory

• “My dad, Lloyd, and all the things he taught me about Lake Ouachita from the time I was 2 years old.”

• “My Lowrance X-28; the amount of detail it displays is unbelievable. I never had to wonder if I was making wasted casts on a spot or not. If the fish were there, the X-28 told me so.”

• “My longtime friend, Larry Ford. He stuck with me like glue from day two on, and he policed all the spectator boats to help keep them from getting too close. He handled it like a true champion.”