Good wood

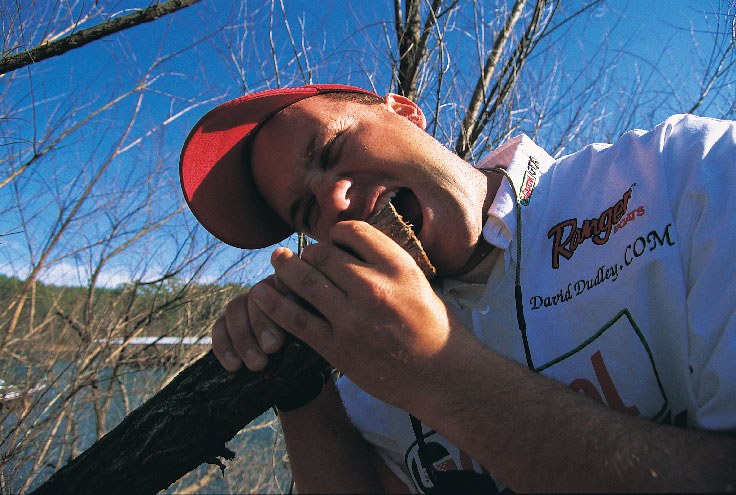

Dudley, Lytle uncover the mystery of vintage wood

After a dismal start to a Wal-Mart FLW Tour event on Georgia’s Lake Lanier, Curt Lytle knew he had to change his approach. At the end of the first day, the Suffolk, Va., pro sat squarely in the back of the pack with two small spotted bass.

“I knew I had to do something different if I wanted to earn a check, so I picked up my flipping sticks and started working docks in the lower end of the lake. I quickly put together a dock pattern that helped me catch five bass that weighed about 10 pounds. I moved up something like a hundred places, which was enough to take home some money,” he says.

So what makes one dock or log better than another? In Lytle’s case, a single ingredient was the key to finding bass. He caught all his fish from docks that had cedar brush piles placed under them. Although Lanier has hundreds of docks, only those with brush surrendered bass. A number of factors play into the bass-on-wood equation, but a few ingredients seem to make a difference, say Lytle and Castrol pro David Dudley, two of the FLW Tour’s top anglers. Whether it’s a dock, a log or another type of wood cover, some hold bass while other, similar-looking types don’t.

“It’s not necessarily the dock or the fallen tree itself that attracts the bass, it’s what’s around the cover. What does the bottom consist of? How deep is it?” asks Dudley, who hails from Manteo, N.C. “Seasonal patterns also play into the picture. It may be the best-looking dock or tree in the lake, but if it’s out on the main lake and the bass are back up in the creeks, it won’t do you much good to fish it. You have to be in an area that has bass to begin with.”

Still, admits the 2002 Ranger M1’s $700,000 winner, some ingredients always seem to contribute to a piece of cover’s ability to attract bass. Sometimes it’s the presence of additional cover such as a brush pile; sometimes it’s the cover’s relation to deep water. Whatever the reason, Lytle and Dudley can eliminate those areas that are less likely to hold bass by considering a few factors.

What’s up dock?

So what does the perfect dock look like? Dudley says there really isn’t a single dock that will hold bass all year, but his vision of a perfect dock has a variety of ingredients. Most important, he says, isn’t the dock itself but what lies beneath it. He typically shuns those built over a muddy bottom.

“My dream dock has a rock bottom underneath it and deep water at the end. The water would be about 5 feet deep under the dock itself. It would also have a wide section right against the bank. The fish are often at the back end of the dock, so that wider section close to the bank will give them shade and cover,” he explains. “You have to remember that the idea of a perfect dock changes with the seasons, however.”

Both Dudley and Lytle favor older docks. Lytle even prefers structures so old that the original pilings have rotted off at the water line and new posts have been installed. In fact, he’ll blow past brand new docks that offer other ingredients that might hold bass.

“It’s been my experience that pressure-treated lumber takes a long time before bass start to use it. Docks made with creosote-treated pilings seem to take even longer,” he says. “The only exception to that is in current situations like tidal rivers. I don’t know why, but bass in tidal rivers don’t seem to mind new wood treated with creosote.”

Lytle’s vision of a perfect dock consists of old pilings combined with new ones, numerous cross braces and perhaps a ladder or two. All that cover provides shade, an important ingredient in summer bass fishing.

“It doesn’t necessarily have to have deep water nearby with that much cover. I’ve caught plenty of bass from 2 feet of water in the summer because the shade provides a comfortable environment,” he says.

So what about brush underneath the dock? Both pros agree that the presence of such cover doesn’t hurt, but the effect it has on bass tends to be a bit overblown. Lytle never hesitates to fish the brush itself, but says that he tends to catch smaller bass from dock brush piles than from the dock structure itself.

Dudley points to a particular dock situation that is often bypassed by many anglers. When he sees one of these structures socked in by thick grass, he’ll do everything he can to plow his way to it. Most other anglers won’t.

“Every dock that is choked with grass is going to have an open spot underneath it because the grass won’t grow in that heavy shade. That’s where the bass will be,” he says. “I do everything I can to get to it and fish it because I know few other anglers will bother to go through the effort.”

Trees, please

When Dudley and his father, James, fished team tournaments on his home water, Virginia’s Smith Mountain Lake, the two would go out and drop trees into the water right before a tournament. Those spots would produce bass the very next day.

“Bass definitely move onto fallen trees as soon as they hit the water. I don’t know why that is, but again, whether or not a bass will use a specific tree has as much to do with seasonal patterns as it does with the tree itself. You have to fish in areas that have bass,” Dudley says.

Lytle also fishes freshly fallen trees, but he shuns green pines, favoring those evergreens only after they lose their needles and secondary branches. He also dislikes pines that still have bark, preferring logs with little or no line-grabbing bark left.

His idea of a perfect fallen tree extends from a steep bank out into deeper water. That gives him the opportunity to fish three different zones: the deep end of the tree, the middle branches and the shallower trunk. When he’s unsure where the bass will be, Lytle typically starts at the deep end and works his way to the shallow end.

“I like logs and trees that are up off the bottom enough so bass can get up under them, even if it’s shallower than others around it,” he says.

Dudley, on the other hand, prefers trees that start out flat against the bottom, particularly during the spawn, and then extend over a ledge. This situation allows him to fish the shallow end of the tree for bass that might be spawning against the cover and allows him to work the end of the tree for post-front bass that may have temporarily migrated out of the shallows onto deeper ledges. Such a tree will be a magnet, he says.

“If I’m fishing a current situation like a tidal river or the river coming into a reservoir, I’m going to look for trees that are right on the bottom. Ideally, the root ball of the tree will be facing into the current and the log will be parallel to the current,” he says. “Not many people know this, but the active bass will be in front of that root ball facing into the current.”

Lytle favors slick logs instead of brushy trees with a tangle of limbs in current situations, saying the lack of cover helps pinpoint the location of fish holding on the log.

“If there are only a few branches, I can cover the whole log in a few casts and find the fish that are on it because, in my experience, the fish will be behind some sort of current break. With a big, brushy tree, I have to spend a lot more time working it to find the bass,” he says.

Every veteran bass angler knows that fish don’t always follow the rules, and that one dock that may not look like it would ever attract a bass may indeed be covered with them. But generally, Dudley and Lytle’s advice is something dedicated bass anglers should consider. Some wood is clearly better than other wood.

Angler profile links: