Cross fire

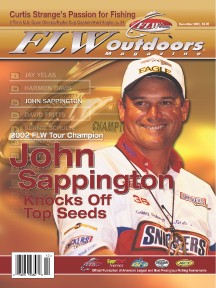

Sappington tops Swindle, wins $260,000 in hot Louisiana sun

The 2002 Wal-Mart FLW Tour Championship might be considered bass fishing’s version of “Mission: Impossible.” At the beginning of the 2002 FLW Tour season, 175 top-level anglers accepted the challenge of fishing their way into the No. 1 spot of the FLW Tour Championship, a feat that promised to pay $260,000 cash.

Before the championship began, 127 of those anglers had already been eliminated. Only 48 pros had fished well enough over six FLW Tour events to qualify for the lucrative championship.

Once those 48 contestants reached the diminutive waters of Cross Lake near Shreveport, La., for the championship, they realized that their quest for the $260,000 had only just begun.

The finalists now had to navigate one of the toughest courses in tournament-fishing history.

For starters, Cross Lake is a small, 8,500-acre lake that is heavily fished. Most Cross Lake bass have had a virtual tour of Wal-Mart’s fishing section by the time they are 16 inches long.

Even if a championship contestant was skilled enough to catch a 16-inch bass, the first thing he would have to do is let it go. That is because Cross Lake has a very tricky trap door: a 14- to 17-inch slot limit. Any bass caught between 14 and 17 inches has to be released immediately. Consequently, anglers could only weigh in bass between 12 and 14 inches or over 17 inches.

Even if a championship contestant was skilled enough to catch a 16-inch bass, the first thing he would have to do is let it go. That is because Cross Lake has a very tricky trap door: a 14- to 17-inch slot limit. Any bass caught between 14 and 17 inches has to be released immediately. Consequently, anglers could only weigh in bass between 12 and 14 inches or over 17 inches.

The final obstacle in reaching the championship crown was an NCAA-style bracket format that pitted anglers against each other in sudden-death elimination fish-offs.

After two days of intense fishing, half the field was eliminated and only 24 anglers remained. Those 24 were matched against each other in head-to-head competition and sent back out on day three to again do battle on Cross Lake. At the conclusion of day three, only 12 anglers remained in competition.

On day four, those 12 anglers were ranked based on their previous three days’ cumulative weight and then pitted against each other for the final payout. The pros seeded No. 1 and No. 2 set out for a shot at the championship’s $260,000 top prize. It was John Sappington of Wyandotte, Okla., and Gerald Swindle of Hayden, Ala., in a head-to-head showdown for bass fishing’s most coveted title.

Cross Lake Conditions

Cross Lake should have been named “About Eight Lake” because it spans about 8,000 acres, is about 8 miles long and retains an average depth of about 8 feet. Many years of silting have rendered the bottom of Cross Lake flat and featureless.

Cross Lake should have been named “About Eight Lake” because it spans about 8,000 acres, is about 8 miles long and retains an average depth of about 8 feet. Many years of silting have rendered the bottom of Cross Lake flat and featureless.

Despite its limited size and rather stark bottom, Cross Lake offers a surprisingly diverse mix of shallow-water cover. The shoreline is dotted with hundreds of docks and piers. The west end of the lake is a flooded cypress swamp where anglers can weave in and out of thousands of majestic cypress trees. The lake also features shallow vegetation, predominantly hydrilla, which grows in 1 to 3 feet of water around the bank.

Sept. 11-14 on Cross Lake provided a perfect definition for the term “dog days of summer.” While a couple of practice days were doused with cooling rains and cloud cover, the tournament days were dominated by hot, hazy conditions. Daytime temperatures hovered between 90 and 95 degrees, and the end-of-summer humidity lingered.

Water temperatures were in the low 90s. Many anglers also noted that the lake appeared to be about 12 to 18 inches below normal and was dropping a few inches each day.

Dominant Patterns

The FLW Tour Championship on Cross Lake was a case study of bass-fishing patterns. Not surprisingly, the two major bass-catching patterns that developed involved docks and cypress trees, but anglers who had a little something extra figured out about the docks and cypress trees were the ones who rose to the top.

In the dock category, Swindle and Pat Fisher of Stone Mountain, Ga., discovered that dock bass on Cross Lake lived extremely shallow. Both anglers revealed that they could finagle out keeper bass that others had missed by fishing in inches of water.

In the cypress trees, Sappington and Dion Hibdon of Stover, Mo., tapped into a particular behavior pattern to catch pressure-wary bass.

Dion Hibdon: 5th place

While Hibdon made a good run at the FLW Tour Championship purse, he admitted that he did not quite have all the pieces of the puzzle to finish first.

While Hibdon made a good run at the FLW Tour Championship purse, he admitted that he did not quite have all the pieces of the puzzle to finish first.

“On a lake with so much pressure, you must have the right `cricket,'” Hibdon said. “Pressured bass are very picky. They want an exact presentation, wobble, action, fall, speed or whatever to make them bite. I felt like I knew how the fish were positioned on the trees, but I was not completely confident that I had figured out exactly what they wanted.”

What Hibdon had discovered in the trees was that bass were using cypress trees to ambush bluegills. On several occasions he witnessed big bass giving chase or wolfing down bream.

This prompted Hibdon to fashion his best bluegill imitator – a Gambler Bacon Rind pitched to cypress trees. His day one efforts netted three bass that weighed 9 pounds, 1 ounce, thanks to a big bass that anchored his catch.

What Hibdon could not get out of his mind, however, was a crankbait. Throughout practice he experimented with crankbaits of all sizes and configurations to no avail.

On the first day of the event, he painfully watched first-round leader Greg Hackney of Oak Ridge, La., sack a heavy limit weighing nearly 16 pounds on a crankbait. At the end of the day, Rick Clunn of Ava, Mo., who had weighed in nearly 10 pounds, asked Hibdon if he could borrow a particular crankbait.

“That really clued me in. When Ricky asks to borrow a bait, you know something’s up,” Hibdon said with a laugh.

Hibdon tried a crankbait the next morning; again, his efforts were fruitless. Although he could not make the crankbait work, Hibdon gleaned a key piece of information from his cranking competitors. He deduced that the fish were not very deep on the trees. Instead of being snuggled into the base of a tree, Hibdon figured they were higher in the water column.

With this in mind, he lightened the sinker on his Bacon Rinds to a 1/8-ounce and a 1/16-ounce. “The ultra-slow fall helped a bunch,” Hibdon said. “I caught a lot more fish the second day; they just didn’t weigh as much.”

On day three, Hibdon was again haunted by the crankbait as he watched Sappington catch bass on a shallow cranking plug.

“I really wanted to commit to the flipping bite, but every time I turned around someone was whacking them on a crankbait,” Hibdon said. “In a tournament like this, you can’t be indecisive, you have to commit, and my mind kept wandering off to a crankbait.”

Hibdon checked in two bass weighing 4 pounds, 13 ounces on day three and two bass weighing 2 pounds, 14 ounces on day four. Fortunately for him, his day four weight was still enough to beat out Aaron Martens of Castaic, Calif., for the fifth-place position.

Pat Fisher: 4th Place

Fisher used a combination of a morning top-water bite and a dock pattern to finish fourth. Every morning he started fishing in the back of the takeoff cove along a shallow grass line with a Pop-R. Fisher claimed an over-the-slot keeper each of the first two mornings to get his first two days started on the right foot.

Fisher used a combination of a morning top-water bite and a dock pattern to finish fourth. Every morning he started fishing in the back of the takeoff cove along a shallow grass line with a Pop-R. Fisher claimed an over-the-slot keeper each of the first two mornings to get his first two days started on the right foot.

After each morning’s top-water flurry, Fisher spent rest of the day dissecting 30 docks in the takeoff cove. While 30 may not sound like many docks, Fisher said he milked each one to the extreme. For his dock presentation, he used a Zoom Tube (black/red flake) with a 1/4-ounce weight tied to 25-pound-test Stren Supertough line.

“I was making two to three flips on each piling,” Fisher said. “I would spend 10 to 15 minutes on each dock.”

What Fisher learned from his painstaking dock work was that the fish were positioned on the shallowest part of the dock. “Most of the dock fish were in less than a foot of water under the catwalks,” he said.

This observation paid off on day two when a continuous train of pros began fishing Cross Lake’s docks. As anglers fished his docks, he noted that they were fishing fast and only focusing on the fronts and sides. On several occasions, Fisher fished behind traffic and lured out keepers that others had missed.

On day one, Fisher weighed in an impressive 11 pounds, 4 ounces. On day two, he weighed in 7 pounds, 6 ounces.

But on day three, Fisher’s stable dock pattern gave way to catching bass between docks on a handmade 1/4-ounce white spinner bait. “My partner caught a couple – bam, bam – on a spinner bait off nothing between docks, so I asked to borrow one of his spinner baits,” he said.

Fisher eventually caught three on the spinner bait – just enough to edge Alton Jones of Waco, Texas, out of contention by a pound.

Fisher was seeded fourth going into the last day, meaning he had a shot at winning $34,500, but he fell short of Brent Chapman from Shawnee, Kan., and settled for $29,000. On the last day, Fisher mustered just three bass weighing 3 pounds, 6 ounces.

Brent Chapman: 3rd Place

Chapman was the only top-five contender who was not focused on a primary pattern. While two of the top five finishers milked docks and the other two committed to cypress trees, Chapman mixed up several patterns over four days to catch his fish.

Chapman was the only top-five contender who was not focused on a primary pattern. While two of the top five finishers milked docks and the other two committed to cypress trees, Chapman mixed up several patterns over four days to catch his fish.

Chapman started each morning in a small grass-laden cove with a 1/4-ounce black Lunker Lure buzzbait.

“Most of the cove was topped-out grass in about a foot of water,” Chapman said. “The key spot was a small 2-foot ditch that ran out of the flat.”

He caught several bass from the morning location, including an over-slot fish on day one and a 4-pound bass on the last day.

Chapman’s second spot was a single large dock that was particularly good to him in practice. He flipped the dock with a 4-inch finesse worm matched with a 1/4-ounce weight and tied to 20-pound-test line.

The Yamaha pro also had a small schooling spot in the cypress trees that he checked occasionally with a small Storm SubWart.

A majority of Chapman’s time was spent pitching cypress trees with the small worm. “In the trees, I tried to key in on the deeper ones, especially where the cypress islands made points,” he said.

Ultimately, Chapman ended the tournament with a three-bass catch weighing 6 pounds, 13 ounces.

Gerald Swindle: 2nd Place

Swindle went to work on Cross Lake’s docks from the minute he got on the lake until the last cast of the last day. Like Fisher, Swindle figured out something about the dock pattern that others had missed – the shallower, the better.

Swindle went to work on Cross Lake’s docks from the minute he got on the lake until the last cast of the last day. Like Fisher, Swindle figured out something about the dock pattern that others had missed – the shallower, the better.

“I tried to stay away from the main-lake docks that had 5 or 6 feet of water under them,” Swindle said. “I focused on the shallow docks in the backs of pockets or on points that had 2 or 3 feet of water on them.”

When Swindle ran out of ultra-shallow docks, he fished the catwalk portions of semi-shallow docks in a foot of water or less.

Swindle picked the docks apart by pitching a Yamamoto Senko, Zoom Centipede and a Zoom Brush Hog to any abnormalities under the docks. He used 3/16-ounce weights on all the plastics and pitched them on 25-pound-test P-Line.

“A metal pole next to a piling, a cross-member, a ladder, PVC poles, even a minnow bucket floating in the water – anything different,” he said. “Standard pilings were unproductive. If there was something else next to a piling, it was an automatic fish.”

A second component of Swindle’s dock pattern was a 3/8-ounce War Eagle double Colorado spinner bait with a No. 3 silver blade in the front and a No. 4 gold blade in the back. He threw the spinner bait while moving between docks.

“I threw it to isolated cypress trees between docks or in the boat slips of the docks that had nothing worth flipping,” he said.

Swindle got off to a slow start on day one with three bass weighing 5 pounds, 6 ounces. “I was dialed in the first day, but I just did not fish as clean,” he said, “I lost two at the boat.”

Swindle picked up momentum on day two when he weighed in five bass totaling 8 pounds, 1 ounce. On the third day, the spinner bait became more of a factor, pushing his weight just over 10 pounds. On the final day, Swindle’s limit was 5 ounces short of topping the weight of Sappington’s four bass.

“I fished as good a tournament as I could have,” Swindle said about his near miss. “I fished a winning tournament; I just did not get the winning check. John was the better man on that day.”

Champion: John Sappington

Sappington fished one small area located on the cypress-rich west end for four days to win the championship. According to Sappington, the area was a key because it was about a foot deeper than the surrounding areas.

Sappington fished one small area located on the cypress-rich west end for four days to win the championship. According to Sappington, the area was a key because it was about a foot deeper than the surrounding areas.

The productive stand of cypress trees was adjacent to several large, shallow grass beds. Sappington theorized that dropping water levels and heavy fishing pressure forced the bass out of the shallow grass beds into the slightly deeper cypress trees for refuge.

“I think my area was replenishing with new fish every day,” Sappington said. “The area was only the size of half a football field. It was getting pressured, but every morning it was like a new crop of fish moved in there. I figured the falling water was bringing them out.”

Sappington also liked the area because a series of cypress tree points and ditches all came together in the same proximity.

“One of the first things I learned in practice was that the fish seemed to be on cypress-tree points,” he said. “But instead of running the whole lake fishing cypress points, I decided to stay put in this one area because seven of these points came together in one spot.”

Sappington began the event by pitching and flipping cypress trees; however, when bass fishing’s biggest guns showed up in his primary area and started flipping cypress trees on the first morning, he knew he would have to alter his strategy.

“I was overwhelmed by the talent in there – Yelas, Nixon, Klein, Blaukat, Hibdon, Biffle – all flipping and pitching trees,” he said.

Though pitching produced a small limit of 5 pounds, 5 ounces, he was disappointed with his start because he had done better in practice.

Sappington’s winning revelation came on the second morning when he saw a big fish boil on a baitfish. He immediately pitched his bait to the boil, but the effort went biteless. He then picked up a handmade crankbait, cast to the same area, and a 17-plus-inch fish engulfed the crankbait.

Sappington went to work probing cypress trees with the shallow-diving plug. Initially, he held his rod tip low to the water, making the shallow-running bait dive to the bottom. On several occasions, as he reeled the bait by a tree, he noticed that fish would, as he put it, “move into the line without contacting the bait.” On one particular cast he actually snagged a bass in the back.

“That told me that the fish were suspended up high on the tree trunks, not down at the base,” he said. “As I was cranking my bait, the line was actually contacting the fish (over their backs) before they could see it coming, and this was spooking the fish.”

Sappington began fine-tuning the angle at which he held his rod to control the exact depth of the bait. When he found the right angle, everything clicked.

On day two, he brought in five bass weighing 8 pounds, 3 ounces. On day three, he caught five bass weighing 11 pounds, 14 ounces, and the possibility of winning $260,000 became tangible.

“Catching three `overs’ on the third day after all that fishing pressure had been through there made me realize I was on the right deal,” he said.

Sappington began the last day with a bang. Knowing exactly how the fish were positioned on the trees allowed him to go to work immediately. He boated four keepers by 8 a.m.

In an interesting twist, Sappington smashed his coveted handmade crankbait against the passenger console and broke the bill off it at 8 a.m. From that point on he never got another bite.

Sappington, who has made his own crankbaits for years, believes that every crankbait has a personality of its own. When he tuned that particular bait before the championship, he knew its wobble was perfect; consequently, he saved it specifically for the final rounds of the big tournament.

“When I broke that crankbait, I kind of lost my mental edge,” he said. “I had some other crankbaits like it, but they did not produce like the one I broke. Maybe it was the bait, or maybe it was just in my head, but they quit biting after that.”

Sappington’s four keepers, weighing 9 pounds, 12 ounces, were enough to hold off Swindle’s five-fish limit.

Sappington accomplished bass fishing’s impossible mission.

Links: