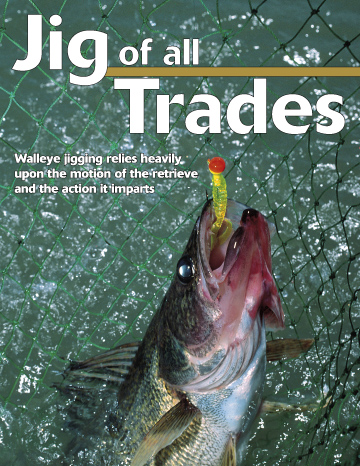

Jig of all trades

Walleye jigging relies heavily upon the motion of the retrieve and the action it imparts

Drag, pitch, pop, rip, lift, hover, shake, swim. What’s the beauty of a jig? You can do anything with it, no matter the sum of its parts.

But while bass jigs are open to incredible interpretation in their makeup and design – or, more precisely, in their dressings, tails and colors (silicone skirts, plastic vs. pork, claws vs. tentacles, blue with silver glitter, black with blue glitter, ad nauseam) – walleye jigs are comparatively simple and straightforward. They’re either light (1/16 to 1/8 ounce), or they’re heavy (3/8 to 1/2 ounce or more). They’re dressed, most often, with bait – minnows, leeches, night crawlers – and increasingly with a short list of options in the soft-plastic department: small, thin worms of 4 inches; slim minnows; and larger, bulkier shad imitations. Their color options fall well short of those used by the bass boys. Brown, black, chartreuse, white and silver with black, green or other muted accents are basically the long and short of it.

All of which means, in walleye fishing, the principles of jigging are condensed to the meat (bait) and the motion (retrieves and subsequent action imparted). When the two categories unite, you’ve got the ways and means to peak the cool-water curiosity of overlyendowed walleyes anywhere and everywhere. Regardless of whether you fish in rivers, in lakes or in reservoirs, the jig is one thing; the action is another, with a roster of options to fit the time and place. Here are some retrieves to consider:

Dragging:

Dragging:

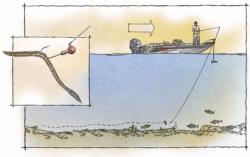

Complicated? Hardly. Dragging a jig means just that – pulling it across the bottom. No hopping, no popping, no lifting. In other words, “no nothing.”

If anything, dragging is best when walleyes are inactive, lazing after the spawn, for instance, or simply unwilling to move much for anything. What’s more, dragging is best where snags are minimal – you’d be foolish to try it on the Detroit River, for instance, with its phalanx of slag, boulders, bedsprings and rebar. On the other hand, rivers or lakes with sand and soft bottom are ideal. Rivers with underwater dunes, such as the Illinois River, site of Wal-Mart FLW Walleye Tour events in 2003 and 2004, are cases in point.

In current, cast straight upstream with a 1/16- or 1/8-ounce jig with a leech, minnow or half a crawler. One trick is to pinch the crawler off in the middle and thread the head up the hook for greater longevity, or try hooking a whole crawler “wacky style” right in the middle, like a bass plastic. Do nothing more than drag the jig downstream, with the current. Then again, you can cast on a slight angle to the current and let the jig bounce downstream.

“It’s a swing method, you could call it,” says Evinrude pro Mark Courts of Harris, Minn. “Let it bounce over sand, rock or whatever the bottom might be – as long as you allow the jig to stay in contact with bottom.”

In still water, let the jig drag behind the boat (great on sand, for obvious reasons) and ease it along at drifting speed. Resist the temptation to “get jiggy with it,” and the jig will do the rest, without any help on your end. What a drag!

Pitching:

Pitching:

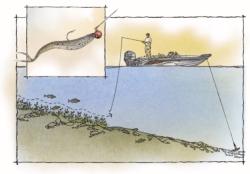

In walleye circles, the terminology is darned near ubiquitous – short-range casting to get after walleyes in shallow water. The depth could be anywhere from a couple feet of water to perhaps 10 or 12 feet on the edge of weeds (that’s shallow for walleyes, not as deep as it might seem for bass). Yep, that’s pitching.

Here’s how it’s done. Cast out, let the jig sink to the bottom, lift it up, and let it sink back to the bottom. Most strikes come on the fall, a truism of walleye angling, but when you vary the intensity and height of the lift (say, 6 inches vs. 12 inches), make a mental note of what gets a response.

While bait is a staple of walleyedom, soft plastics are emerging in such close quarters, where casts seldom exceed 40 or 50 feet. Besides, meddlesome maulers – perch, bluegills, etc. – remove bait like pickpockets. Enter plastics in the form of a Berkley Power Minnow or half a Gulp! crawler, cast out on FireLine, without stretch for ripping free from weeds, let fall and pop. Let it drop back to the bottom and pop the rod again. A fish either will tweak it on the way back to bottom or will be there when you pop it again.

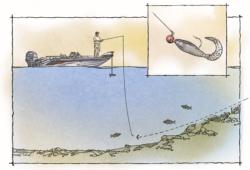

Ripping:

Ripping:

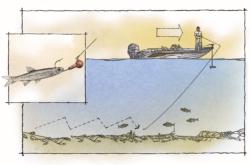

With plastic rather than a tender crawler, you can get medieval on a jig with speed and snap. When pitching, boost up one size from the jig you’d use for dragging with bait – say, from 1/8 to 1/4 ounce – and when you cast the jig and let it hit bottom, rip it up a foot or two and let it sink. Repeat. Don’t be shy.

The same goes for a modified trolling technique, one that works with plastics and even minnows – that is, when the minnows are hooked securely. Call it snap-jigging, if you will, and take a 3/8-ounce jig on 10-pound monofilament, not braided line (too much action with it), with a long (at least 6-foot, 6-inch) spinning rod with a fair amount of backbone. Next, get yourself a minnow (if not plastic); put the hook in its mouth, out its gill, up through the belly and out the back. Then crank up the kicker motor to about 1 mph and start trolling. Let out enough line so that when you rip the jig and let it fall, you’ll hit bottom with each drop of the rod.

“You wouldn’t believe how fast you can move these jigs and still catch fish,” says professional guide and tournament walleye angler Jeff Taege of Rhinelander, Wis. “I call it `maximum power jigging.'”

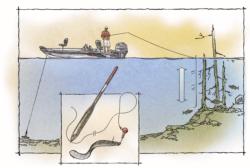

Lift and hover:

Lift and hover:

When John Kolinski of Menasha, Wis., won the 2003 FLW Walleye Tour event on the Illinois River by catching sauger, he did it with his penchant for vertical jigging. Vertical means just that – straight below the boat and not off to the side on an angle, a mission accomplished with bursts on a bow-mount electric trolling motor. Kolinski lifted the jig and held it. Lifted and held. Lifted and held.

“You can lift a jig up 6 inches, 1 foot or 2 feet,” Kolinski says. “If walleyes are not aggressive, you can hold it off the bottom as long as six seconds. Most of the time you’re going to lift, hold for a couple of seconds and drop back to bottom.”

How long you hold is a function of the walleye’s mood, which varies day to day, even hour to hour.

“Sometimes if I’m popping the jig up, I’ll hold it and shake it to mix it up,” Kolinski says. “You can’t always do the same thing all day.”

This is to say, “lift and hold” is open to interpretation. Sometimes they want it popped to its apex a given distance above bottom. Sometimes they want it when you shake it. Sometimes they want it hovering 3 inches up and not a foot.

Swimming:

Swimming:

Nothing could be easier than casting out a jig and plastic, then simply reeling it in. Like ripping, swimming is excellent around weeds, where you can key in on active walleyes that are in the weeds to feed in the first place. The most well-rounded jighead for almost all instances is a 1/4-ounce ballhead, the go-anywhere, do-anything jig of all things walleye. Once again, in the realm of swimming, plastic trumps bait.

“Typically, if I’m going to swim a jig, it’s with plastic,” Taege says.

Specifically, the styles most in vogue for swimming are plastic shads, paddle tails and curly tailed grubs – plastics with action when retrieved. Jigging would be something of a misnomer, because there’s neither jigging nor jerking involved. Rather, you cast out, let sink to bottom and start reeling so it stays above the weeds. Swimming, in fact, is so productive a pattern that, in addition to casting crankbaits, it helped Rick Walter of Casper, Wyo., win the 2003 FLW Walleye Tour event on Devils Lake, N.D. Besides, out on Devils, plastics are far more affordable than $5 crankbaits when northern pike attack. They’ll let you sift through pike, though with plenty of retying when the needle-nose critters saw you off.

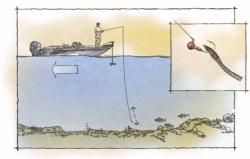

Slip-bobber:

Slip-bobber:

Well, it might be a bit of a stretch to call bobber fishing jigging. How about “autojigging?”

The way it works is like this: A jig goes on the end of your line, a bobber partway up, with a sliding stop in order to keep the jig at a given depth. Could be 10 feet, could be 15. At the very least, it’s adjustable with a stop on the line, above the bobber, to keep the jig from falling any farther. In most instances, the perfect distance above bottom, set with an ice-fishing plummet, is 6 to 12 inches.

On the FLW Walleye Tour, bobber central is Devils Lake, which is filled with trees following flooding that started in the ’90s and tripled the lake from its original 50,000 acres. But with walleyes thriving in a combat zone, you’ve got to be able to go in and get them.

Enter the slip-bobber, rigged on heavy line to wrestle walleyes out of the timber. A lighter leader, meanwhile, is connected to a swivel. “That way, when you do bust off, your bobber doesn’t go drifting away in the wind,” Taege says. With a main line of 10-pound Berkley FireLine leading to a barrel swivel, your leader can be tied with 2 feet of 8- and even 10-pound monofilament. (Ten-pound FireLine is far stronger than 10-pound mono and is thus able to break the leader easily when you bust off.)

For the business end of the mono, a little jig of 1/16 ounce, with a couple of split shots above it for added weight, provides a bit of color (pink, chartreuse, green) when launching bait such as a leech or a crawler hooked wacky style into the thickets.

“With a bobber, I get carried away,” says Mark Courts, whose two top-five FLW Walleye Tour finishes on Devils in as many years have come bobber fishing. “I put it in the worst of worst places, even if I’m going to wind up breaking off a fish.”

If the jig is up, you can do it however you wish.

Dragging, pitching, popping, ripping, lifting, hovering, shaking, swimming. The beauty of a jig is its versatility with a leech, crawler, minnow or plastic. From there, the action is all yours.