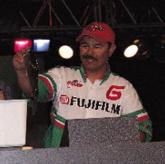

Waits’ baits

Eddie Waits plugs into an ancient pattern to win the All-American

Eddie Waits of Pine Bluff, Ark., sat alone in a Chinese restaurant in Shreveport, La., having dinner and reflecting on his roller coaster-like Wal-Mart Bass Fishing League season.

After fishing all year in the Arkie Division and failing to qualify for the regional, Waits went to the Chevy Trucks Wild Card Regional on Kentucky Lake. At the Wild Card, Waits looked strong after day one; he was in third place with 12 pounds, 8 ounces.

On the second day, however, motor problems sought to dash his last hope for an All-American berth. Because of his motor, Waits was forced to idle 30 miles back to check-in. Frustrated and fishless, he was ready to wave the white flag.

“I was giving it up after the Wild Card,” Waits said. “I had been trying to do this (make the All-American) for eight years, and it just wasn’t happening. I had pretty much decided to put it on the trailer and hang it up for a while.”

Apparently Waits has a bigger heart than he does an ego. Since the boat ride had consumed most of the day, neither Waits nor his partner had fished much. Waits said he felt for his co-angler, who had hardly fished at all. So just before throwing in the towel, Waits stopped to let his co-angler make a few casts before check-in. Waits made a few casts, too.

Like the answer to a desperate prayer, a 1 1/2-pound keeper bass grabbed his crankbait. At the weigh-in, that single fish kept Waits from sliding out of an All-American berth. Waits finished sixth and was the last man to qualify for the 2002 All-American.

A few months later, he was at Cross Lake practicing for the All-American in a borrowed duck boat with a tackle box full of his late father’s old wooden crankbaits.

A few months later, he was at Cross Lake practicing for the All-American in a borrowed duck boat with a tackle box full of his late father’s old wooden crankbaits.

As he mulled over the recent events in his life, the waitress brought him a fortune cookie that read: “Participation in sports may lead you to a lucrative career.”

The 47-year-old All-American qualifier found a bit of solace in the prognostication printed on the sliver of paper.

Cross Lake conditions

Cross Lake, located just a long cast from downtown Shreveport, is a relatively small lake of 8,500 acres. The lake lies east to west and is approximately 8 miles long and 1 mile wide. The predominant bass hideouts in Cross Lake are docks on the developed eastern end and thousands of cypress trees in the swamp-like western end.

Beneath Cross Lake’s dark, tannic waters is a featureless bottom that averages 8 feet. Manmade boat canals and natural creeks, which used to provide deep channels, have silted in over the years.

What makes fishing on Cross Lake so difficult, however, is not shallow water or a contourless bottom, but a stringent slot limit. All-American participants had to release immediately all bass between 14 and 17 inches; they could only keep bass that were 12 to 14 inches or bass over 17 inches.

The tricky slot limit became the primary nemesis for all 100 All-American contestants, forcing anglers to develop fishing strategies around the slot rule.

Some anglers, including eventual winner Waits and runner-up Greg Gutierrez of Red Bluff, Calif., fished exclusively for big fish. Some anglers, like third-place finisher Steve Kennedy of Auburn, Ala., targeted fish that were under the slot, while others, like Ricky Smith of Collinsville, Miss., (fourth) and Terry Tucker of Gadsden, Ala., (fifth), decided to go for the best of both worlds by devising both small-fish and big-fish patterns.

During practice, many All-American qualifiers reported good catches from Cross Lake, but sometime during the two-week off-limits period, the summer doldrums put Cross Lake bass in a bad funk.

When anglers returned for the All-American June 5-7, things had changed. The fish were not as cooperative, especially “unslotted bass.”

Practice

Perhaps the angler spending the most time on Cross Lake before the cutoff was Waits. He logged a total of 18 practice days on Cross Lake, searching for winning patterns. Most of that time was spent fishing from a borrowed aluminum duck-hunting boat because his own bass boat had motor problems.

A native of Arkansas, Waits grew up fishing oxbow lakes on the Arkansas and White rivers. He found Cross Lake to be very similar to those oxbows where his dad had taught him how to fish big wooden crankbaits around cypress knees for big bass.

From the first day of his practice on Cross Lake, Waits targeted over-slot bass. “I fish for nothing but big fish,” Waits said about his All-American game plan. “That’s all I’ve done my whole life.”

In developing his big-fish pattern on Cross Lake, Waits estimates that he experimented with 600 to 700 different baits during his 18 days of practice. Waits eventually discovered an “old-bait” pattern: the older the bait, the better it worked.

The gem of Waits’ old-bait pattern was a Creek King, a 45-year-old wooden cranking plug with a metal bill. Waits claims that he only used the plug briefly on three different occasions during practice, but each time he brandished the ancient plug, he caught multiple big fish.

“The big fish would just eat it up, no matter where I was on the lake,” Waits said. “Each time I fished with it, bass, from 3 to 5 pounds, would eat that bait so well that I had to get needle-nose pliers to remove the plug from the back of their throat.”

How they fished

Terry Tucker had a two-prong approach for Cross Lake that targeted both under-slot fish and over-slot fish. The smaller-fish pattern was fishing docks with a pair of finesse jigs. Tucker used a 1/4-ounce Bo’s jig (camouflage) and a 3/16-ounce P.J.’s jig (green pumpkin) to catch finicky bass from Cross Lake’s most pressured bass structure – docks and cypress trees in 1 to 2 feet of water. He teamed both jigs with Seismic chunks (black/red glitter) for increased vibration.

Tucker’s over-slot pattern was flipping a Zoom Baby Brush Hog (black/red glitter) pegged to a 1-ounce weight into thick clumps of reeds. He flipped the heavy bait on 60-pound-test braided Spider Wire with a Kistler Hydrilla Gorilla flipping stick.

Tucker targeted docks and trees in the morning and then flipped thick reeds in the afternoon. He got off to a slow start on day one. On day two, however, everything went according to plan. Tucker caught four under-slot fish early using the two finesse jigs and then flipped up an over-slot fish on the heavy tackle in the afternoon. His catch weighed 7 pounds, 13 ounces.

Tucker fished for all the marbles on the last day. He abandoned his jig fish and went straight to flipping the reeds for big fish. His effort netted two bass weighing 4 pounds, 2 ounces.

Ricky Smith made three weekend-long trips to Cross Lake to feel it out before cutoff. From those trips, Smith decided that he would intentionally fish areas and techniques that discriminated against slot fish.

Smith wanted to find an obscure pattern that would favor non-slot fish. He eventually found exactly what he was looking for. The area was a barren flat, 2 feet deep, with scattered patches of grass. He fished the area with a 1/2-ounce Rat-L-Trap tied to 20-pound-test Stren Line.

“I was looking strictly for a reaction bite from smaller fish,” he said. “I would burn the Rat-L-Trap past the clumps of grass and make the fish bite out of reflex rather than hunger. This appealed to the smaller fish; I never caught a slot fish all week.”

Smith accompanied his small-fish pattern with a big-fish pattern, one that provided two 17-inch-plus fish during the event. He located one small break offshore that held a single piece of brush. The spot was small, but it had all the right ingredients for a kicker fish on Cross Lake. He fished the brushy break with a Strike King Series 5 crankbait on Stren 10-pound line once a day.

Smith’s two-fold equation worked flawlessly. On day one, he caught four smaller keepers from the scattered grass on the Rat-L-Trap, then visited the big-fish break and caught a kicker for a stringer weighing 8 pounds, 3 ounces.

That weight alone would have qualified Smith, but he wanted to make sure he made it to the finals. On day two he caught two small fish from the flat and then another 17-inch-plus kicker from the big-fish spot.

On the last day, Smith again burned the Rat-L-Trap on the flat for four fish less than 14 inches and then headed for his big-fish spot. Just like clockwork, the kicker fish bit – and then pulled off.

Smith, however, is not the least bit fazed about losing the fish or missing the $100,000 winner’s check. “I did not go to the All-American for the money; I went for the memories,” he said. “My two daughters rode out there with me, and my wife came out later in the week. We all had an incredible time together. There has never been a more enjoyable week in my entire life. The only reason I wanted to win was that it would have put me in a better position to be a positive role model and spokesman for the sport. But other than that, I would not sell the memories from that week for any amount of money in the world.”

Steve Kennedy targeted under-slot fish at Cross Lake and his plan worked, almost to the tune of $100,000. He was the only angler to catch a limit all three days of competition. While the small-fish game plan was a sure ticket to the finals, it left him a little short on the last day.

“I stumbled upon a bunch of little bank-runners,” he said. “I caught more than just about everybody every day. I had six keepers, and I actually culled a fish in the finals, but I still only caught 4-14.”

Leave it to the Californians to come to a lake, cast aside conventional angling techniques and apply some West Coast pizzazz. Such was the case with California angler Greg Gutierrez at Cross Lake.

Gutierrez, however, did not use a delicate drop-shot tied to 6-pound test on a wispy spinning rod. To the contrary, he used a Sumo Frog tied to 80-pound-test braided line on stout action rods.

The Californian also found his productive area with an innovative approach – from the air.

“When flying into Shreveport we flew over Cross Lake,” he said. “Quickly studying the lake from the air, I noticed that all of the tributaries coming into the lake were brown except for one feeder head, which had a green color to it. The creek was tucked in behind a massive stand of cypress trees. I made a mental note of it and decided to use my practice day to check it out.”

On the single official practice day Gutierrez ventured back into the cypress swamp until he found the green-colored tributary. Watching his water temperature gauge, he noticed that the water was almost 10 degrees cooler once he got back into the creek. Also, the matted weeds, which lined the shallow creek channel, were set up perfectly for scooting a top-water frog along the surface. After a few promising blowups on the plastic frog, Gutierrez had a game plan.

He caught two fish over the slot and two fish under the slot for a total of 12 pounds on day one. The Sumo Frog (white) provided all of Gutierrez’s catch for the day.

Though 12 pounds was 4 pounds more than he needed to make the cut, the Californian decided to catch just one bass from his secluded creek on day two for security.

He returned to the creek on day three and caught two fish under the slot on the Sumo Frog, and on his way back to check-in, he caught a 3-pound bass on a Bandit Series 100 crankbait. His three fish weighed 5 pounds, 6 ounces, enough for second place.

“The vegetation on Cross Lake reminded me of the California Delta back home,” he said. “We use the Sumo Frogs on the matted vegetation there. Since it is a Western bait, I figured that Cross Lake bass had probably not seen one.”

When Eddie Waits discovered that older, wooden cranking plugs were the secret to catching Cross Lake’s over-slot fish, he went on an old-bait scavenger hunt, borrowing old plugs from family members and friends.

Waits lined his All-American tackle box with borrowed antique tackle. He had Creek Kings from his father and grandfather. Then he stocked a few original Bombers, Lucky 13s, and Cotton Cordell Big O’s from his father-in-law. Another good friend loaned him some 30-year-old Bagley Balsa B crankbaits.

What Waits ended up with was not so much a tackle box, but rather a fishing heirloom full of family lures, a tackle box that held long, storied histories of catching fish.

“All I had in that box were old plugs from family and friends,” Waits said. “Every time I opened that tackle box I thought about all those folks and how much they have helped me and supported me, especially my wife and three kids. I thought about my father – he gave me the gift of the great outdoors.”

Waits won the tournament with only six fish. On day one he caught one big bass weighing 4 pounds, 5 ounces on his father’s Creek King that he had used in practice.

On day two, he switched from the Creek King to a 30-year-old Cotton Cordell Big O crankbait that he had borrowed from his father-in-law. That bait produced two fish, one over slot and one under slot, weighing a total of 4 pounds, 7 ounces.

On day two, he switched from the Creek King to a 30-year-old Cotton Cordell Big O crankbait that he had borrowed from his father-in-law. That bait produced two fish, one over slot and one under slot, weighing a total of 4 pounds, 7 ounces.

In the finals, Waits stuck with the Big O, which produced two under-slot fish and a 3 1/2-pound kicker that gave him the victory.

Waits said he concentrated on shade lines of big cypress trees and docks for his catch. He specifically used a short, 5-foot-6-inch rod with a pistol grip to make accurate casts up under trees and along docks.

Waits still gets emotional about his All-American victory and feels indebted to those who helped get him there, especially a young man named Jesse Levey.

“Ten years ago, my good friend Robert Levey was killed in a car accident,” said a tearful Waits. “One thing I promote is parents taking their kids fishing. So when Robert died, I took his son, Jesse, under my wing and took him fishing because he didn’t have a daddy that could. This spring, Jesse was killed in a car accident, too. That flat-bottom duck boat I practiced out of was his. When I needed a boat to practice out of, Jesse’s mom said it would only be right if I practiced out of Jesse’s boat. That’s another thing that makes this win so special.”

Jeremy Ives of Burgaw, N.C., claimed the co-angler title in the 2002 Wal-Mart Bass Fishing League All-American on Cross Lake. He pocketed $50,000 for the win.

Ives fished a Hawg Caller Log Crawler creature bait (black/red glitter) behind his pro partners to score a two-day total of 7 pounds, 11 ounces. He rigged the bait with a 3/8-ounce screw-in rattling sinker and fished it on 17-pound-test line.

Ives fished a Hawg Caller Log Crawler creature bait (black/red glitter) behind his pro partners to score a two-day total of 7 pounds, 11 ounces. He rigged the bait with a 3/8-ounce screw-in rattling sinker and fished it on 17-pound-test line.

Ives targeted docks with the Log Crawler and said that fishing slower than his pro was the key to getting more bites. All of his fish were over-slot bass.

The 28-year-old angler has been fishing competitively for two years, and he plans to switch to the boater side of the BFL circuit next year.