Parsing the waters

Nationwide walleye scene experiencing fabulous growth

Despite the altered states of today’s U.S. walleye fisheries, most for better and far fewer for worse, the waters are like the Energizer Bunny: They keep going and going and going. Indeed, whether they have record high or low water levels, fewer and smaller fish compared with roistering historic peaks, higher water quality through conservation and more fish through stocking, the nationwide walleye scene is in a heartening stage of revival.

All things considered, a single, straightforward principle rules the contemporary walleye world. To crib (and twist) a phrase from our 41st president, it’s the environment, stupid. In some cases, nature has the upper hand; in others, human influence trumps most other factors. In the case of the Great Lakes, a discordant, indeterminable union of exotic species from distant seas and improving water quality leaves the future open to speculation, even among biologists who spend their lives studying it.

Take Lake Erie, the otherworldly apex of Planet Walleye, where 10-pounders have heretofore been the rule, not the exception. But times are changing with younger, smaller walleyes – fewer of them, too – that nevertheless constitute the premier walleye fishery anywhere.

The naturally spawned giants of up to two decades ago have ostensibly been caught or died of old age.

“The ’82 and ’86 year classes are starting to dwindle,” said Jeff Tyson, fisheries biology supervisor for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources’ Sandusky Fisheries Research Unit. “We’re moving toward a younger age structure in the population.”

In fact, the copious 5- to 6-pounders are attributable to big-time spawning success in 1999 – yep, you see a bunch of fish that size – more fish, now approximately 3-pounders, are in the pipeline from the 2003 spawn. What’s more, Erie’s seemingly indomitable population from the late ’80s, an estimated 90 million, is now pegged at 25 million, with at least some of the reduction blamed on the proliferation of more than 150 exotic species from distant waters as far as the Caspian Sea, including the ubiquitous zebra mussel.

“It’s a wonder they have persisted in the lake for 6000 years,” Tyson said, adding, “It’s a phenomenal fishery. A couple of year classes could put us back in the late ’80s.”

The phenomenal Erie fishery will be back on the FLW Walleye Tour’s 2005 schedule, with good reason. So, too, will Devils Lake, North Dakota, a watery curiosity plagued by more than a decade of record rainfall. The catch? Devils Lake has no outlet to drain it.

Therefore, Devils has gone berserk, with the lake tripling in size to 150,000 acres following a wet cycle that started in 1993. According to a prediction by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Devils could explode to more than 500,000 acres by 2030.

For at least an interminable interim, the fishing should continue at its breakneck pace, turning out staggering numbers of 4- to 6-pounders. The reason behind them is the accompanying fertility, as well as room to grow, that has come with waters that have usurped forests, farmlands and, alas, homes and farm implements. And the trees projecting everywhere – it’s almost difficult to see the, um, water through the trees – hold Devils’ abundant freshwater shrimp and, in turn, walleye that eat them.

For at least an interminable interim, the fishing should continue at its breakneck pace, turning out staggering numbers of 4- to 6-pounders. The reason behind them is the accompanying fertility, as well as room to grow, that has come with waters that have usurped forests, farmlands and, alas, homes and farm implements. And the trees projecting everywhere – it’s almost difficult to see the, um, water through the trees – hold Devils’ abundant freshwater shrimp and, in turn, walleye that eat them.

But while there’s water, water everywhere in North Dakota, and even northeast South Dakota, only a state away is downright parched. Lake Oahe, just upstream of Pierre, S.D., on the Missouri River, and the other two upper reservoirs could reach record-low levels. If a forecast from the Army Corps of Engineers comes true, Oahe could dip more than 4 feet below the record set in late 1989. As a result, even while the walleye are there, a key source of their food is dwindling.

That would be the rainbow smelt, a baitfish from the Atlantic Ocean that was stocked upstream of Oahe, in Lake Sakakawea, to provide fish food. The smelt spread downstream to Oahe, their population cresting at 1.1 billion in 1996 before crashing to 45 million in 1999. Yes, the smelt are gone or going, and so are many of the launch ramps left high and dry because of water levels that are about 20 feet below normal.

Although the Missouri River basin is dry, a couple of wet years (which are sure to happen sooner rather than later) will raise the water levels to normal pool. When water rises to pre-drought levels, vegetation that has been growing on the dry banks (and the associated insect and other animal life) will be flooded, increasing the fertility of the lake and likely creating a boom in quality fish.

Yet, one more place has little trouble with water, and the fishery has responded in kind. Try the Mississippi River, whose water quality is improving in large part because of the Clean Water Act. Besides that, rainfall continues in northern Minnesota, the source of Big Muddy, and continues filtering its way downstream.

And while the fishing for last year’s FLW Walleye Championship out of Moline, Ill., might have been substandard due to recent rainfalls and muddy water, walleye are thriving in the river, with 40-fish days possible on some of the pools, including the thoroughly stocked Pool 14, where Nick Johnson won the most recent championship and $300,000.

And while the fishing for last year’s FLW Walleye Championship out of Moline, Ill., might have been substandard due to recent rainfalls and muddy water, walleye are thriving in the river, with 40-fish days possible on some of the pools, including the thoroughly stocked Pool 14, where Nick Johnson won the most recent championship and $300,000.

“The Mississippi River is in a comeback,” said Evinrude pro Tommy Skarlis. “This is a peak period, one of the heydays, some of the best fishing I’ve ever seen on the river.”

Sure enough, most places are up and a few are down, but Walleye Nation is, by and large, prospering. The overwhelming reason? It’s the environment, hombre.

Take 5

Top walleye spots you don’t want to miss

1. Chautauqua Lake, N.Y.

1. Chautauqua Lake, N.Y.

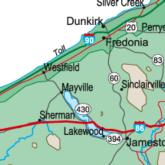

In southwest New York, 13,000 watery acres with points, weedlines and deep water were first juiced with walleye plants at the turn of the last century and were more recently boosted by record spawns in the ’90s. The deeper, clearer north half is more conducive to bottom bouncing and open-water trolling, the southern half more suited to shallow-water jigging with plastics. Worthwhile checking are Warners Bar, Long Point and Predergast Point. Chautauqua County Visitors Bureau: (800) 242-4569. M&M Sports Den: (716) 664-5400.

2. Lake Erie, Ohio/Mich./Pa./N.Y.

Erie’s prodigious schools – according to some estimates, half the walleyes in North America – begin a counterclockwise circumnavigation of the inland sea with the start of summer. Even so, the Western Basin, around the Bass Islands in western Ohio, continues to give up numbers of walleyes year-round in an open-water troll-a-thon. Go with spinners and crankbaits (high-action Storm Hot `n’ Tots, Reef Runner Deep Little Rippers, Storm Deep ThunderSticks) for suspended fish. Farther east, from Cleveland into the waters of western New York, pick off the deeper, migratory schools with cranks and spinners on leadcore line. The fish could be down 55 feet over 100 feet of water. Ottawa County Visitors Bureau (Port Clinton, Ohio): (800) 441-1271. Lorain County Visitors Bureau (Lorain, Ohio): (800) 334-1673. Chautauqua County Visitors Bureau (Dunkirk, New York) (800) 242-4569.

Erie’s prodigious schools – according to some estimates, half the walleyes in North America – begin a counterclockwise circumnavigation of the inland sea with the start of summer. Even so, the Western Basin, around the Bass Islands in western Ohio, continues to give up numbers of walleyes year-round in an open-water troll-a-thon. Go with spinners and crankbaits (high-action Storm Hot `n’ Tots, Reef Runner Deep Little Rippers, Storm Deep ThunderSticks) for suspended fish. Farther east, from Cleveland into the waters of western New York, pick off the deeper, migratory schools with cranks and spinners on leadcore line. The fish could be down 55 feet over 100 feet of water. Ottawa County Visitors Bureau (Port Clinton, Ohio): (800) 441-1271. Lorain County Visitors Bureau (Lorain, Ohio): (800) 334-1673. Chautauqua County Visitors Bureau (Dunkirk, New York) (800) 242-4569.

3. Leech Lake, Minn.

3. Leech Lake, Minn.

At more than 100,000 acres in Minnesota’s north woods with a range of depths reaching more than 100 feet, Leech holds walleyes that are shallow, deep and everywhere in between. Cases in point: shallow sandgrass and emerging cabbage weeds, rock humps and shoreline points sliding into the depths, open water where walleyes are on the roam to nowhere. Tip: Leech kicks tail on the windy side of the lake, where waves send baitfish into orbit and put walleyes on the feed. Leech Lake Area Chamber of Commerce: (218) 547-1313. Reed’s Tackle: (218) 547-1505.

4. Lake Sharpe, S.D.

4. Lake Sharpe, S.D.

With 80 miles of Missouri River impoundment between the Oahe dam and Ft. Thompson, Sharpe is a riverine walleye piñata, spilling out incredible numbers, with 80 possible per day (few exceeding 20 inches, though). Hit the upstream side of points near the creek channel, where Berkley Power Minnows produce big time. Other patterns: trolling the bluffs with shad baits and pulling bottom bouncers and spinners downstream slightly faster than current speed. Pierre Chamber of Commerce: (800) 962-2034. South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks: (605) 773-3381.

5. Lake Winnebago, Wis.

Opportunity knocks everywhere on central Wisconsin’s shallow, enormous Winnebago, a system with the namesake lake and upriver waters of Lakes Poygan, Winnecone and Butte des Morts. The deepest, ‘Bago itself, bottoms out at 22 feet, where an open-water fishery jams on crankbaits trolled high in the water column behind boards over the mudflats. In the shallows of Poygan and Butte des Morts, pull shad-shaped crankbaits (blue holographic No. 5 Rapala Shad Raps imitate juvenile sheepshead) in 6 feet of water or poke around in a foot or two of water on the fringe of cane beds with jigs and plastics or live bait. Oshkosh Convention Bureau: (877) 303-9200. Pioneer Resort & Marina: (800) 683-1980.

Opportunity knocks everywhere on central Wisconsin’s shallow, enormous Winnebago, a system with the namesake lake and upriver waters of Lakes Poygan, Winnecone and Butte des Morts. The deepest, ‘Bago itself, bottoms out at 22 feet, where an open-water fishery jams on crankbaits trolled high in the water column behind boards over the mudflats. In the shallows of Poygan and Butte des Morts, pull shad-shaped crankbaits (blue holographic No. 5 Rapala Shad Raps imitate juvenile sheepshead) in 6 feet of water or poke around in a foot or two of water on the fringe of cane beds with jigs and plastics or live bait. Oshkosh Convention Bureau: (877) 303-9200. Pioneer Resort & Marina: (800) 683-1980.