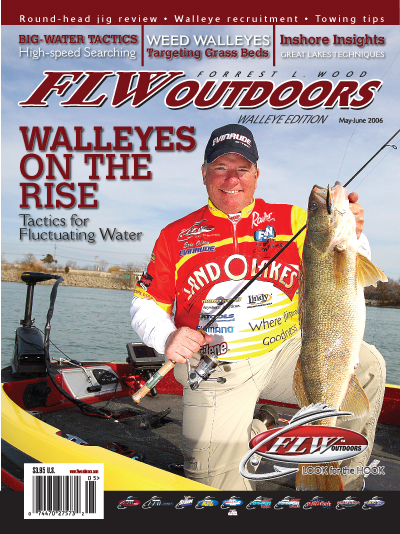

Adapting to river fluctuations

How walleye pros handle rising and falling water

“The only thing constant in life is change.” That seems an appropriate mantra for walleye anglers when fishing the country’s larger river systems.

Unlike reservoirs and natural lakes where water levels remain fairly stable and changes occur gradually, large rivers are subject to rapid fluctuations. The rise and fall may be the result of the annual rainy season or a large storm in a distant part of the watershed. In other instances, flow changes may be due to demands for power generation or irrigation.

No matter what the reason, anglers must be prepared to meet the challenges of change. Here’s how two Wal-Mart FLW Walleye Tour competitors adapt to the walleyes’ shifting location and mood swings brought on by fluctuating water.

River a rising

Robert Crow, a six-year veteran of the FLW Walleye Tour, feels very confident in fishing rivers. After all, his home water is the Columbia River. In addition to seasonal fluctuations related to weather events, the Columbia rises and falls on a day-to-day basis due to power generation.

According to Crow, the formula for location under regular moderate fluctuations isn’t that hard to figure out. Small rises that increase current velocity in particular locations where walleyes feed will send both baitfish and ‘eyes seeking less severe flow. For example, fish on midriver humps move to the backside of those humps when flow increases. They also move into the bays or the mouths of tributary rivers where current is slower. When the level drops to normal, fish return to their previous locations.

But what about a flood event where water rises more than a couple feet? Do walleyes hunker down or move?

“In a river system that has a flood plain, walleyes move shallower with the advancing water. That isn’t because the fish realize the water depth has increased overhead in the main river. Walleyes really don’t know or care what the water level is. Rather, the ‘eyes are following forage,” Crow said.

Baitfish recognize an increase in current velocity in the main river and, being a smaller species, they are not capable of maintaining favorable positions in that flow. Furthermore, as water moves into dry channels and over banks, fresh food sources are introduced for baitfish. Therefore, as baitfish move shallower for food, walleyes in turn follow their prey.

Baitfish recognize an increase in current velocity in the main river and, being a smaller species, they are not capable of maintaining favorable positions in that flow. Furthermore, as water moves into dry channels and over banks, fresh food sources are introduced for baitfish. Therefore, as baitfish move shallower for food, walleyes in turn follow their prey.

“As fish move into newly flooded areas, they still remain current-oriented but do not fight strong currents. Instead, walleyes position themselves at a current break, waiting for their meals to come by,” Crow said.

Pro Eric Olson, a resident of Red Wing, Minn., acquired his insights on rising water through his years of experience on the Mississippi River.

If water rises slowly, Olson notes that feeding shelves develop with walleyes moving a few feet shallower at a time, staging at different depths. He says if you do not pay close attention to subtle rises, you will likely end up fishing where the walleyes were a day ago.

“You’ve got to locate landmarks on the shoreline to quickly tell you how fast the water level is transitioning,” Olson said. “This may be measured by a mark on a tree trunk or even a stick stuck in the bank. I discovered about seven years ago how a subtle change of a foot will make a huge difference in where the fish are located. If they are at the top of a main river breakline and the water creeps upward during the day, those fish may move several feet farther in to feed. If you continue to fish the same shelf where you caught them earlier, you are going to be missing the fish entirely.”

On most rivers there is a significant amount of brushy growth along the banks, such as willows and other scrubs. Olson explains that walleyes will move into this cover as water rises. You can find them hanging tight to bushes that are impacted by current, often side by side with smallmouth bass.

“Many anglers are surprised to learn just how shallow walleyes may be under rising water events. On tributaries of the Mississippi, I’ve found walleyes tight to flooded tree roots in 6 inches of water with their backs sticking out of the water. Rather than a specific depth, the two keys to catching them are finding baitfish and good water clarity,” Olson said.

Olson says river anglers must be aware of the water clarity card. “Along with bottom structure and current flows, clarity is the third element in rivers.”

Walleyes do not favor muddy water when it comes to feeding. Of course under a high water event, clear water is relative to the conditions. Therefore, if you can find clearer inflowing water (feeder creek, tributary river, marsh seepage, etc.), expect to find walleyes. Olson acknowledges that fish will set up along a clarity seam in the clear water to ambush prey moving from the dirtier water.

Presentations for rising water

Presentations for rising water

Crow is quick to point out that walleyes are more aggressive feeders under rising water than falling water. “The fish are advancing and locations will change daily, perhaps hourly. Therefore, I choose to cast crankbaits and cover lots of water to find them. My recommendations include slender ones like Shad Raps, Reef Runners and Wally Divers.

“The water is usually dirty, so dingy-water colors like chartreuse, reddish brown and other dark colors are going to be productive. However, don’t overlook white. An all-white crankbait is a surprisingly good muddy water color.”

Olson concurs with crankbait presentations for rising water. “Absolutely. Shad Raps are my choice. I’ll use one of three color patterns: blue, chartreuse or craw. I employ either a No. 7 or No. 5 Shad Rap, depending on wind conditions. Accurate casts are a must. The bigger bait gives you a little better accuracy in wind.

“You’ve got to stay in contact with the break. Most anglers cast perpendicular to the shore cover and retrieve the bait straight back, therefore having the bait in the strike zone only briefly. I emphasize casting as parallel to the cover as possible – a sort of diagonal retrieve that will intercept more fish.”

Olson allows his boat to drift downstream while he is casting downstream and retrieving a No. 5 Shad Rap against the flow, thereby driving the bait deeper for a longer duration on the retrieve. With an up-current wind, he goes to the No. 7 Shad Rap for more cast control.

“However, when confronted with a down-current wind, the boat moves very quickly, so I need to slow it,” Olson added. “That is when I put the bow-mount motor on constant, while angling my casts more upstream.”

If Olson discovers walleyes have actually moved into brush or wood cover, he breaks out a jig and worm. His choice is a Lindy Munchie Thumpin’ Ringworm on a Lindy Max Gap Jig. He favors this particular head because it has a red hook and a wider-than-normal gap with a slightly bent-out point. “The advantage of an outward-bent point is if a fish barely inhales the jig, you are going to hook it,” Olson said.

Receding water

As water recedes, walleyes of course slide back toward the main channel. But our experts do not look at falling water with the same hopeful expectations as rising water.

“Falling water is tougher to fish, in part because walleyes are not as aggressive,” Crow said. “A mass movement of fish occurs during rising water. But when the water begins to fall, walleyes break up into smaller groups and filter back over a longer period of time. There are multiple areas that can hold fish, and you’ve got to work hard to find them. Just keep working newly formed current breaks as the water drops.”

“Falling water is tougher to fish, in part because walleyes are not as aggressive,” Crow said. “A mass movement of fish occurs during rising water. But when the water begins to fall, walleyes break up into smaller groups and filter back over a longer period of time. There are multiple areas that can hold fish, and you’ve got to work hard to find them. Just keep working newly formed current breaks as the water drops.”

One of Crow’s favorite tactics is to locate flooded “ridges” and fish their backsides. Included in his definition of ridges are slight rises of hard material that funnel back toward the river, underwater points coming off the shore, as well as islands submerged by the high water.

“Basically, any significant structure that deflects current, thereby creating an eddy on the downcurrent side, I refer to as a ridge,” Crow said. “These are the sites where walleyes stack up as water recedes. I’ll troll upstream, bringing my crankbait in behind the ridge and work it around or over the crest. If water clarity is improving, I’ll switch to natural patterns, such as shad or silver and blue.”

Olson often finds large river flats that have significant current passing over them become a holding area for baitfish and walleyes after a high-water event.

“These flats are most often comprised of sediment associated with some sort of outlet, such as a tributary creek,” Olson said. “Main-river currents erode away at these flats causing shelves to form at different depths. The fish hold on a breakline and cycle up to feed on baitfish in the shallower water. As water continues to recede, walleyes will fall back to the next breakline farther out on the flat.”

As fish slowly retreat across these submerged flats, it may take considerable time for them to return to their original locations in the main river.

Like Crow, Olson depends on pinpoint trolling of crankbaits. “With water dropping and current slowing, I start off trolling at regular speed with No. 5 Shad Raps to locate fish,” he explained. “If I don’t get a bite, I bump the speed up, trolling 3 to 3.5 mph upstream. If I get a strike, I switch to vertical jigging to stay over the fish better. But if the fish don’t react to vertical jigging, I go back to trolling and increase the speed even more. I’ll eventually trigger those fish with the right speed.”

Sauger sensibility

Anglers often find saugers and walleyes living side by side. Some claim saugers react the same as walleyes under rising water conditions, but not everyone agrees.

“Saugers will be extremely aggressive one time, and no where to be found the next time. Saugers – like women – are often difficult to figure out,” joked FLW Walleye Tour pro Steve Lamb, of Nashville, Tenn. According to Lamb, since the average sauger is smaller in size than a walleye, few tournament anglers put effort into catching them – unless fishing a river pool where saugers far outnumber walleyes.

Jim Duckworth, a multi-species guide from Tennessee, focuses on Cumberland River saugers during certain times of the year. “The main difference between saugers and walleyes is the part of the water column they inhabit. In the main river, walleyes tend to ride a little off the bottom, while saugers stay glued to the bottom.

“If a river is rising and filled with trash, saugers will get behind rocks to avoid debris and simply shut down – I’ve witnessed this time and time again while working as a commercial diver. But if the rising water is debris-free, saugers will turn on. On a falling river, the bite slows way down, and sauger strikes will feel more like a wet leaf stuck to your hook.

“I troll crankbaits on a rising river, but go to a jig and minnow on a falling river. And if the river is trashy, I don’t go at all,” Duckworth concluded. “However, if I absolutely must fish for them under this condition, I use live bait on the bottom at the head of a pool with a dead-stick rod.”