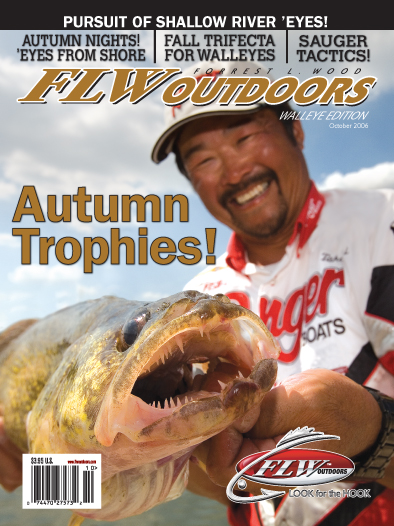

Rigging for late-fall hogs

Live-bait rigging in October means trophy time to many walleye anglers

If they could, FLW Outdoors walleye pros Pete Harsh and Dan Stier would make one adjustment to the yearly fishing calendar: “If we could take October and make it eight months long, that would be just right,” Harsh said.

Fall is a time when their boats may be the only ones in sight, even on heavily pressured waters. The kids are back in school and most boats are parked in their garages. Many anglers have already traded their fishing rods for their bows, rifles or shotguns for various hunting seasons.

But there’s another important reason these pros love the fall. It has to do with what’s going on below the surface of the water.

All summer long, anglers had to be satisfied with catching mostly small fish while the real trophies – the 10s, 11s, 12s and even larger – were roaming open-water chasing schools of suspended baitfish. That made the giants hard to find and harder still to convince to take a lure trolling by at 2 mph.

But, all that changes as the days shorten and temperatures cool. The biggest walleyes in the system sense winter’s approach. Mother Nature whispers – it’s time to fatten up for the lean times to come. Mature females also start to burn energy to make eggs for the spawn next spring. As a result, their metabolism has never been at a higher pitch all year than it is right now. They become vulnerable as they move to classic structures to intercept baitfish.

It’s trophy time. “The big fish are just like bears,” Harsh said. “They’re trying to gorge and store up fat for the winter. This is the time of year when they are eating machines.”

It’s trophy time. “The big fish are just like bears,” Harsh said. “They’re trying to gorge and store up fat for the winter. This is the time of year when they are eating machines.”

That still doesn’t make it easy. Catching huge fish requires what Harsh calls “unlocking the keys to the walleye kingdom.” That is location, presentation, timing, plus the little secrets that help trigger bites.

“These fish are 8- to 20-years old. They didn’t get that old by being stupid,” Harsh said. “Like the television show, these are the survivors. They are wary. You have to fool them.”

Two other factors add to the challenge. One of these factors centers on the fact big fish don’t travel in large schools. A handful may hunt together. One boat on big water in search of a relatively small target means trophies can be hard to find. And with the exception of low-light periods, fish in the clear-water systems of the North haunt great depths. As a result, presentations must be done with pinpoint accuracy. Fall fishing can mean taking a big chub down 30 to 65 feet and putting it in a space the size of a bathtub.

The combination of deep water and precision leads Harsh and Stier to resort to rigging most of the time. This tactic may yield only a handful of bites each day. But, each one could be the biggest fish of the year – or a lifetime.

The setup

Rigs are all basically the same – a barrel swivel, a slip sinker, a snell and a hook. It’s how they’re put together and modified to meet conditions that makes all the difference. In this case, the rig must handle both big bait and big fish.

Trophies are haunting the depths to intercept fat-rich forage like tulibees, white fish and smelt that have been growing all year. Predators want the most energy returned for the least energy expended. Many anglers make the error of using minnows 2.5 to 3.5 inches long. Harsh and Stier use chubs 5 to 8 inches long. If you’re thinking that’s just too big, the pros disagree. “Even a 2-pound walleye will just drill an 8-inch chub,” Harsh said.

Big bait requires a sinker equivalent to an anchor to keep it down in the strike zone, so leave those 1/2-ounce sinkers at home. For Harsh, it’s time to bring out the 3/8- to 1-ounce Lindy slip sinkers for smooth bottoms or No-Snagg sinkers for rocks. Stier tends to go even heavier, and 3/4 ounce sinkers and 1 1/4-ounce sinkers are his choice.

Harsh drills out the hole in walking sinkers to let line slide through easier after a walleye takes the bait. If the fish feels resistance of any kind, it may drop the chub. Both men add a bead to stop the sinker from getting lodged on the knot.

Harsh keeps the snell length to 3 feet or less during cold fronts. He’ll stretch it to 4 to 5 feet if the weather is stable and the water is clear. Heavier weights and shorter snells allow him to position the bait where he wants it.

Stier keeps leaders to 3 feet in the rocks he loves, but he’ll use one 7 feet or longer on smooth bottoms.

Stier keeps leaders to 3 feet in the rocks he loves, but he’ll use one 7 feet or longer on smooth bottoms.

Harsh uses a No. 1 Kahle Eagle Claw feather-light hook. The goal is to keep the chub lively and unhurt until the big crunch comes. He hooks the chub through both lips. The bait lives longer that way. Walleyes take their meals head first, so the odds of a hookup are greater than hooking the bait between the dorsal fin and tail.

Stier uses a 1/0 or 2/0 VMC. Why so big? The hook gap must be wider than the chub’s head to get the point into the walleye.

Rod choice is critical. It must have backbone, yet the tip must be light enough to vibrate when the chub starts to panic when a walleye moves close.

“When a walleye comes around, they go nuts. My minnow is freaking out. Knowing that your minnow is going wild down there takes patience, but it is an exciting way to fish,” Harsh said.

A 7-foot medium-action rod is a great choice. Monofilament in 6- or 8-pound test is also an excellent line choice.

Steep drops are the key

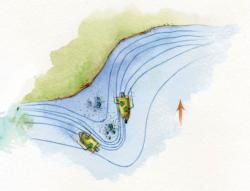

Except during low-light times when fish are shallow, fall fishing focuses on steep drops related to classic structures, which provide both food shelves on one hand and deep water on the other. On natural lakes, look for sharp breaks near the deepest water in that section. On reservoirs, places where the channel swings close to a point are the ticket.

Make no mistake, “steep” means exactly that. One foot out from the top of the structure equals one foot down. That’s the proper angle for defining a “steep” break. Species like tulibees, whitefish and smelt swim along deep breaks until they encounter a point where they must turn out to go around or go over the top. That’s where big walleyes will wait in ambush.

“The points are like a bottleneck. Everything that runs into them has to turn out. It’s just like hunting big deer in a funnel area,” Harsh said.

Stier adds another feature to the mix – rocks. Make that boulders. “If I find big rocks, I find the big fish wherever I go. A break of 38 feet to 22 feet with rock on the tip; that’s a great spot,” he said.

Harsh motors over a break until he sees baitfish on his sonar screen. Slowing, he continues his search until he sees marks that signal big walleyes. He’s learned over time not only to identify walleyes but how big they are and how many there might be.

“At those depths, you are going to see the fish,” Harsh said. “Many times, you can make the call. There’s Miss Piggy; you can sit on her until she bites.”

It’s not that simple when fishing big rocks. Walleyes can hide. In that case, Stier cruises the structure looking for big rocks and baitfish. He enters a waypoint on the GPS when he sees what he’s after. Even in rocks, a few walleyes may slide into the open where the electronics can detect them.

Harsh has trademarked the name “Mr. Tiller” for a reason. It’s situations like these where his choice of a Ranger 620T shines. Back-trolling slowly over the drop allows him to explore different depths. Even in high winds, he can hold and hover his boat directly over fish.

Stier uses the gasoline kicker on the transom of his Ranger 620VS in stiff wind and waves. But he sticks with the electric trolling motor on the bow in a light or moderate breeze.

Drift socks are excellent tools to help you control your boat in the wind. Attach a drift sock to the bow of the boat when back-trolling or attach it to the mid-ship cleat when drifting.

Harsh and Stier both emphasize that it’s important to stay vertical over the bait. You can target a certain fish on the screen and stay with it until it bites. But, it may not be alone, and once you catch the first, how will you find the second if your rig was off somewhere 50 feet away from the boat?

Both men also agree on another key detail. Working the bait from shallow to deep water yields more strikes. Walleyes feed by looking to the front and upward. The chub swimming overhead is just too hard to resist, even for a walleye that just ate a 2-pound tulibee.

“They take it before they know what’s happening,” Harsh said.

“That’s the golden rule,” Stier agreed. “It’s just phenomenal how important this is when you are working up and down the break where the majority of the time the bites happen when you’re coming down.”

The chub will scout for you. If Stier doesn’t feel the bait dance as he moves through a spot, assume walleyes are absent or inactive. It’s time to move on.

Stier recommends a slow, sweeping motion to keep the chub off the bottom. More often than not, strikes come as the bait moves back. Sometimes, the sensation feels like something hit the chub with a hammer. Don’t set the hook right away.

“I might sit on a bite for two or three minutes,” said Harsh, who can recall watching walleyes feed in the shallows as he peered over the side of the boat as a boy. They’d hold a sunfish for minutes before turning it headfirst and swallowing.

“It’s just like you eating a big steak. They won’t wolf it down in 15 seconds,” Harsh said.

Other times, heavy weight seems to appear on the other end of the line when a walleye is playing with its dinner. Stier begins to reel slowly to force the fish to react. The walleye will be fooled into thinking the bait is getting away.

Indeed, Stier reels slowly on any strike. The goal is to get the weight off the bottom so you have a direct line to the walleye before setting the hook. The rod tip will bob a few times until it dips down toward the surface of the water. That’s when the weight is out of the way.

Horsing big fish to the boat is not a good idea. Play them slowly. Stier remembers getting good advice from fellow pro Gary Roach a few years ago.

Horsing big fish to the boat is not a good idea. Play them slowly. Stier remembers getting good advice from fellow pro Gary Roach a few years ago.

“He said, `Dan, you have to learn to back-reel. Don’t count on the drag. It’s mechanical, and they can fail.’ But, even when back-reeling, the drag is still there to help,” Stier said. Figure on 10 minutes to get a true trophy to the net.

Big fish require a big and strong net. A net with a minimum of a 22-inch hoop and a long 6- to 8-foot handle is the only way to get these big fish into the boat. Always net the fish head first, and always anticipate that last-second dive to the bottom.

“If they are hooked properly, they won’t break the line,” Harsh said. “Lighter rods will absorb the shock. There is no other way of fishing that’s more fun.”

The word is spreading

“There were times on Lake Oahe where I was the only boat out there,” said Stier, who hails from South Dakota. “Nowadays, people have found what an untapped resource late-fall fishing can be. Once they experience it, they’re hooked.”