Crankbaits to the max

The first step toward becoming a crankbait master is learning how every variable affects the system

————————————–

Editor’s note: Learn more about FLW Outdoors Magazine and how to subscribe by clicking here.

————————————–

I have a favorite crankbait. It dives to about 10 feet, has a green-and-white shad pattern with iridescent sides, and I’ve seen some good fish eat it on nearby Kentucky Lake.

But like any outdoor writer, I’m not content to throw that one crankbait every time I think I’ve found a cranking-plug bite. No, I’ve got to test, toy with and examine as many crankbaits as I can get my uncalloused, little, office-bound hands on.

I admit, I may be better off learning the tendencies and abilities of a few crankbaits, rather than testing so many. But I enjoy comparing body styles, bill shapes, lengths, weights, sounds, buoyancies and every other characteristic of the lures to all others. Heck, I’ve even gone so far as to buy some balsa to start tinkering with my own designs.

Some may ask why I go through the trouble. But that’s easy. I don’t agree with the thought that one crankbait can do it all. And I don’t want to believe four or five can do it all either. To me, there are so many variations of crankbaits that I’m convinced if a person could learn how they perform and in what situations they excel, that person could go out every day and get on a crankbait bite. Thus, he or she could take crankbait fishing to the max.

However, I also admit there are people who don’t have the same opinion as me, such as David Wright of Lexington, N.C, who is considered an expert on fishing crankbaits and who uses a refined crankbait system.

“I normally don’t use rattling crankbaits,” Wright said. “I almost always use wood plugs … I do not like fluorocarbon. I’ve tried fluorocarbon, but I’m a mono man … I don’t like fiberglass. I’m a graphite man.”

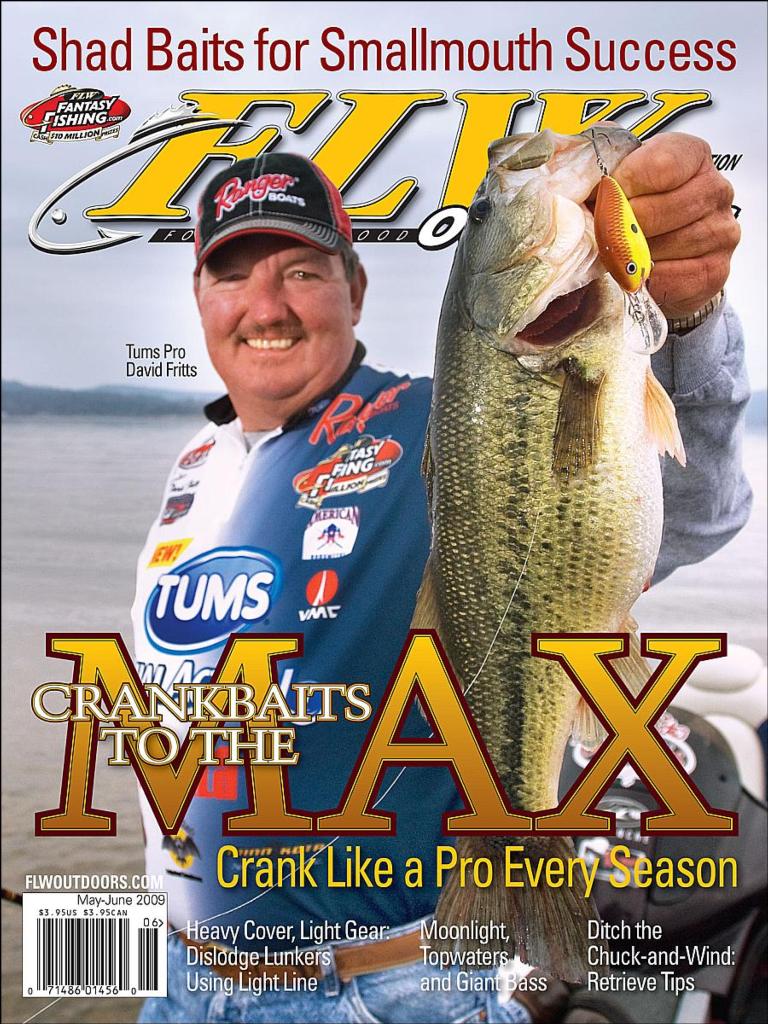

Sure, Wright’s comments stung a little. I mean, he has won nine FLW Outdoors tournaments. And he’s been cherry-picking entry fees from less-ade?quate crankers in the Carolinas for a few decades. And he learned to fish crankbaits at the same school as the oft-titled “Crankbait King,” Tums pro David Fritts, also of Lexington, N.C. And he’s pulled more fish from the water with a diving plug than I could ever hope.

But I’d venture a guess he did a good bit of experimenting over the years to arrive at his cranking system. And he, along with Fritts and Chevy pro Anthony Gagliardi of Prosperity, S.C., knows what works where, when and why through hours spent with a cranking rod.

Luckily, they shared their thoughts. School is now in session.

Rattles vs. no rattles

A rattle does two things to a crankbait: It adds sound, and it adds vibration. Gagliardi believes there are times when each may have an advantage.

“I do use both,” Gagliardi said. “My determination most of the time is water clarity. If I’m fishing real clear water and the fish are fairly pressured, I would use one that doesn’t rattle. If the water is a little colored, most of the time I do use one that rattles.”

Wright has a different theory. Three decades ago, he and a friend experimented with a rattling and rattle-free crankbait. The test involved his friend’s submerged ear and Wright retrieving the lures nearby. Based on the results, they found little difference in the sound of both approaching crankbaits, and although his friend has no lateral line to test vibration, Wright has since put little thought into using rattling crankbaits.

Floating vs. suspending

Floating crankbaits seem to be far more popular than suspending versions. The main reasons for that are simple. First, crankbaits are classically made of balsa, a material that floats. Second, when a floating crankbait contacts a potentially bait-stealing piece of cover, it has a chance to make it through without getting hung because the buoyancy helps it to “walk” over. And if it runs hard into or under a limb, stopping the retrieve for a second will let it float up or “back out” of the snag.

Suspending crankbaits are more common during the cold season or any time a slow retrieve or even a pull-and-pause retrieve is needed to get sluggish bass to bite. Rather than floating out of the strike zone when the lure stops, a suspending crankbait stays nearly in place.

Some pros also rely on them to reach greater depths. Buoyancy is the enemy of a deep diving depth, thus, suspending crankbaits can be worked deeper than floaters.

Plastic vs. wood

Crankbaits have been made from dozens of wood species by tinkerers trying to whittle their way to the perfect lure. But like with most aspects of fishing, modern technology is taking over. With computerized molding systems, plastic crankbaits can now be weighted, shaped and tested quickly, easily and inexpensively into the most effective patterns.

Fritts catches fish on both types in any season, but in the coldest and warmest months, when it’s toughest to make fish bite, he leans toward subtle wood. Plastic is used in addition to wood in spring and fall when fish are aggressive, because plastic crankbaits are often louder and flashier than wooden models.

Square-bill vs. round-bill

Of the classifications mentioned here, this is perhaps the one that creates the most extreme divide. Standard theory goes: Square-bill crankbaits are used for fishing shallow around thick wood or grass cover. Round-bill crankbaits are used for any other diving application, but primarily for deeper work.

Generalizations aside, square-bill crankbaits really are more suited for shallow work because they can rarely dive deeper than about 6 feet. But they are by no means the only option around shallow cover.

“When a round-bill hits something, it turns and goes around it most of the time,” Fritts said. “A square-bill is totally different. You can pull it up to something, and you can almost make it hit it twice. It deflects totally different.”

Fritts prefers the deflection of a square-bill during hot or cold periods in shallow water. But in his opinion, a round-bill is easier to keep free of hangups, and it’s his main option.

Flat side vs. round side

The jury is still out on the best applications for flat and round crankbaits. Body shape is often linked to bill shape, and thus, is decided accordingly. But if not, it seems to be a matter of personal preference when to choose one over the other.

“Your flat-sided ones are going to give you a little bit tighter wobble,” Gagliardi said. “Your rounder ones are ones that seem to have a bit wider wobble. I like the tighter-wobbling crankbaits in cold temperatures. The wider-wobbling crankbaits seem to do better in the warm months.”

Slow-roll vs. burn

The most productive retrieve speed can not only change throughout the day, it may change depending on which fish on a spot eyeballs the lure. But in general, fast retrieves catch aggressive fish that bite out of reaction, and slow retrieves are for finicky fish not willing to chase.

Many pros are progressing to using a fast retrieve for both offshore and shallow shoreline cranking. A fast retrieve presents the lure to more fish in the allotted time – an advantage in tournaments. However, most agree there are seasons and situations that call for a slower retrieve, and they characterize speed choice with their own rules of thumb.

“Every crankbait I fish in the warmer months, I’m going to fish pretty fast,” Gagliardi said. “In wintertime and early spring, I slow the retrieve down.”

Constant contact vs. sudden impact

One of the easiest ways to know a crankbait is in the strike zone is to make constant contact with the bottom. And for tournament pros who fish fast for reaction bites, it’s one of the best ways to cover water quickly with a crankbait. They use long casts so the time the lure spends in the strike zone is maximized, and it works.

But what many anglers don’t know is constant contact may result in a crankbait that doesn’t create the action it is intended to create. It also makes it difficult to get good hookups when fish can’t strike from below.

“There are a lot of baits out there that when they get on the bottom, they won’t even run,” Wright said. “I call it `breaking away.’ It will get to the bottom and curve up to the left or right.”

Deep divers with large, broad, shovel-shaped lips seem to be the worst culprits, and shallow divers with small bills the most cooperative.

To avoid the situation altogether, shoot for a sudden impact and deflection.

“I’m going to throw my crankbait out there, and I don’t want it to hit anything except something sticking up,” Fritts said. “That is the best way to fish a crankbait.”

Stop and go vs. go, go, go

Crankbait fishing doesn’t have to be a constant chuck-and-wind affair. Fish may prefer a steady grind one day, but they may respond to a crankbait’s sudden change of direction the next.

“Unless the water is cold, I don’t ever really stop my crankbait much,” Gagliardi said. “The only time I ever stop my bait is if I hit something.”

But in cold water, Gagliardi often employs a sweeping retrieve with a suspending crankbait. It keeps the lure moving slowly and in the strike zone for fish that are slow to take the bait.

“It’s almost like fishing a Carolina rig, but a little faster,” he said. “I pull the crankbait with my rod, take up slack and pull more.”

Similarly, Wright rarely stops reeling his crankbait, at least on purpose.

“Ninety percent of the time it’s just a straight retrieve,” Wright said. “But you have to be careful when you say `straight retrieve.’ When I hit cover, my rod bends, my line stretches, and I guarantee the crankbait almost stops completely.

“I don’t do stop-and-go, except for the fact that my crankbait does it on its own when it hits cover.”

For Fritts, however, a slowdown or stop of the crankbait right before it hits a piece of cover is a good thing.

“I try to make the bait quit vibrating,” Fritts said. “I call it `pausing’ a crankbait. I raise my rod and pull the bait to me, but I don’t want it vibrating. I want to slow that bait down to a slow-roll. I think it gives it a more lifelike action.”

Jointed vs. solid

Jointed crankbaits have yet to catch fire and take over much of the solid, one-piece crankbaits’ domain. There is no season a one-piece model won’t work. But there is a time when a jointed crankbait may work better.

In early spring, when fish are aggressive and in tune to bait migration and the water is dirty, the unique swimming pattern of a jointed crankbait puts off more vibration than many solid crankbaits. Some also create unique noises when the two halves click together. Both factors make them suited to attract fish.

Graphite rods vs. fiberglass rods

Fiberglass is becoming a product of the past in the fishing-rod world. But to dedicated crankbait anglers who mastered the trade when fiberglass was in, making a change in an effective system would be like removing a link from a chain. The whole thing would come undone, wouldn’t it?

For Wright, that’s not the case at all. Because he uses a stiff rod with only a bit of softness in the tip, and, more importantly, he wants the most sensitive rod he can find, a graphite rod is the only choice for him.

Fritts disagreed. He prefers the same style fiberglass rods he has used for decades, relying on the American Rodsmiths David Fritts Cranking Series rods.

“Graphite is fast,” Fritts said. “If a fish is sucking that bait in, your rod tip tries to pull it away from the fish before he ever gets a bite on it. Glass is slower. Fish can get your bait and get clamped on before your rod pulls it away from them.”

Fluorocarbon vs. monofilament

Crankbait anglers have been some of the most stubborn to accept fluorocarbon into their tackle boxes. And Wright and Fritts are still among that group. They both use monofilament and don’t seem eager to change.

For Wright, it’s about rod selection. He uses stiff, heavy rods, which require a forgiving line, and mono fits that description. For Fritts, it’s about durability. Fluorocarbon is tough and doesn’t stretch, but a hard-pulling crankbait will try to stretch it all day. Eventually, the line may break. Monofilament, however, can stretch repeatedly and still hold up.

Monofilament is also buoyant. Want to fish a diving crankbait shallower than its normal range? Switching to a large-diameter monofilament will help.

Advantages of fluorocarbon come for anglers wanting to fish deep. Fluorocarbon sinks when it hits the water, and it is generally smaller in diameter than the same pound-test in monofilament. Both of those factors allow crankbaits to dive deeper with fluorocarbon than with monofilament of the same test. The added depth may be small, but if an extra foot is needed, fluorocarbon can provide.

Cover also plays into the decision. No-stretch fluorocarbon helps to feel every bump, tick and wobble around cover. But pull a lure into wood too fast, and the line can be too unforgiving to avoid a snag.

High-speed reel vs. low-speed reel

Low-speed reels typically have about a 5:1 retrieve ratio or slower. They are still quite popular for crankbaits and are especially suited for handling the torque of winding slow all day with big-lipped offshore divers. But not all pros are willing to give up their speedier options.

Those who toss large plugs and grind bottom at a high rate of speed often use reels in the range of  6.4:1. The high speed may put some wear on the angler by the end of the day, but the extra speed helps to burn big lures. The same goes for shallow cranking, in which case some use reels closer to 7:1.

6.4:1. The high speed may put some wear on the angler by the end of the day, but the extra speed helps to burn big lures. The same goes for shallow cranking, in which case some use reels closer to 7:1.

A few thoughts from Fritts

Coffin bills

A coffin-bill crankbait, also known as a four-corner-lip crankbait, is much like a square-bill crankbait in that it has an unusual deflection when it hits a piece of cover based on which part of the bill contacts first. Many can dive deeper than the average square-bill, and they are often used around laydowns and stumps.

Like square-bills, Fritts reserves them primarily for summer and winter. But rather than picking a set scenario for when to use one, consider it another “deflection option” to experiment with when cranking cover.

Rod angle

Proper rod position is important for sensitivity and control with a crankbait. Fritts keeps his rod about 2 or 3 inches off the water and slightly off to one side or the other. Doing so, he always has a tight line to the lure to feel every wobble and to easily jerk, pause or pull around cover.

Slow floaters and sinkers

“Floating” and “suspending” categorize most crankbaits. But there are a few others that can be considered.

Fritts likes a crankbait with very little buoyancy, what he referred to as a “slow-floater.” The lure doesn’t suspend, but it doesn’t float away from cover too quickly to look unnatural.

Two categories of rattlers

Fritts prefers rattling crankbaits for nearly all his fishing. But he divides the noisemakers into two categories: those with little rattles and those with big rattles.

Big rattles make crankbaits loud, and they are used when fish are feeding. Little rattles are more subtle for less active fish, and they get the majority of the work, including nearly all the work deeper than 10 feet.

A quick jerk

Fritts’ pausing technique is good for enticing moderate bass, but it’s difficult to master. Another option is the opposite. When the lure hits cover – a stump is the best example – give the rod a slight jerk. The sudden jolt can draw active bass to bite, but get used to using a plug knocker when trying the technique.